Rhyming Translations of Qurʾanic Sūrahs

by Devin Stewart*

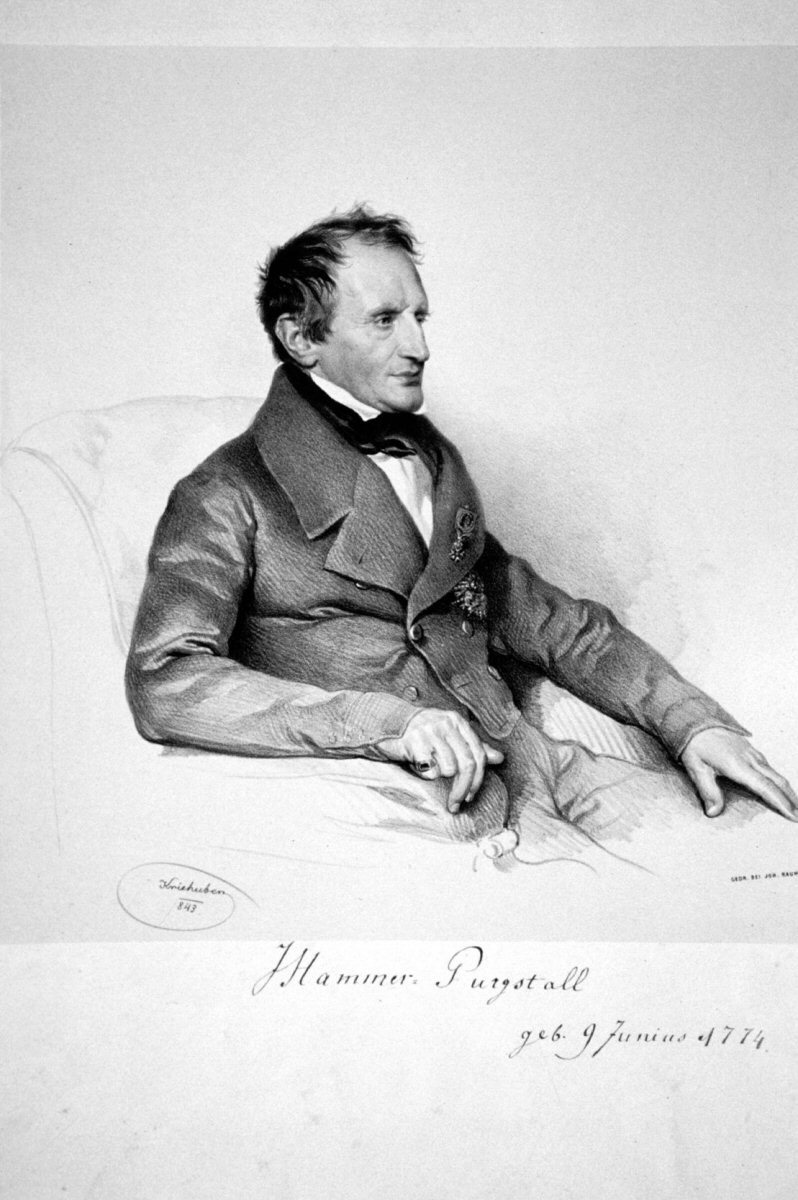

A curious fact has recently come to my attention, and I suppose it may be news to most readers of this blog. I was surprised to learn that the Austrian Orientalist Baron Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1774-1856), best known for his voluminous and detailed history of the

Lithograph portrait of Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, by Josef Kriehuber, 1843; image accessed from Wikimedia Commons.

Ottoman Empire, translated forty surahs of the Qur’an in 1811 [Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, “Die letzten vierzig Suren des Korans. als eine Probe einer gereimten Uebersetzung desselben,” in Fundgruben des Orients 2 (Vienna: Anton Schmid, 1811-12): 25-46.] The evidence of his profound engagement with the Qur’an in addition to his other variegated interests is worthy of note, but the most curious feature of his translations are that they rhyme, endeavoring to represent the original Arabic rhyme in German. It is well known—to Germans, at least, perhaps less so to others—that Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), an extremely talented polyglot scholar, poet, and translator, produced a rhyming translation of most of the Qur’an (published posthumously, in 1888). We can compare both scholars’ translations of Sūrat al-ʿĀdiyāt:

Hammer-Purgstall:

Die C. Sura. Die Wettrenner

- Bey den Pferden, die im Wettlaufe rennen!

- Unter deren Hufen die Kiesel brennen,

- Die sich am Morgen wetteifernd zum Laufe drängen,

- Die in Staubwolken daher sprengen,

- Und die feindlichen Geschwader trennen,

- Der Mensh ist gegen seinen Herrn undankbar!

- Er selbst bezeugt es als wahr.

- Er liebt zu sehr Reichtum und Pracht,

- Weiss er denn nicht dass am Tag, wo erhellt wird der Gräber Nacht,

- Und wo, was in dem Busen Schlägt, wird an Tag gebracht;

- Weiss er den nicht dass an jenem Tag der Herr har auf Alles Acht?

Friedrich Rückert:

- Sure, “Die Jagenden”

Im Namen Gottes des albarmherzigen Erbarmers

- Die schnaubenden, die jagenden,

- Mit Hufschlang Funken schlagenden,

- Den Morgenangriff wagenden,

- Die Staub aufwühlen mit dem Tritte,

- Und dringen in des Heeres Mitte!

- Ja, der Mensch ist gegen Gott voll Trutz,

- Was er sich selbst bezeugen muß,

- Und liebet heftig seinen Nutz.

- O weiß er nicht, wann das im Grab wird aufgeweckt,

- Und das im Busen aufgedeckt,

- Daß nichts von ihnen ihrem Herrn dann bleibt versteckt?

With the exception of Shawkat Toorawa’s recent rhyming translations of surahs into English, I am aware of no rhyming translations in any other European languages. I have several questions for the readers of this blog:

- Which of the above German translations is more successful? Why?

- Are there any other rhyming translations of the Qur’an out there in French, Italian, Spanish, etc.? (There is another German one, by Martin Klamroth.)

- Why might German translators be more apt to pay attention to rhyme than translators working in other European languages?

- Why do English translators tend to be so reticent about rhyme? Pickthall, for example, cannot even bring himself to use the word “rhyme” in his introduction:

There is another peculiarity which is disconcerting in translation though it proceeds from one of the beauties of the original, and is unavoidable without abolishing the verse-division of great importance for reference. In Arabic the verses are divided according to the rhythm of the language. When a certain sound which marks the rhythm recurs there is a strong pause and the verse ends naturally, although the sentence may go on to the next verse or to several subsequent verses. That is of the spirit of the Arabic language; but attempts to reproduce such rhythm in English have the opposite effect to that produced by the Arabic. Here only the division is preserved, the verses being divided as in the Qurʾan and numbered.Are attempts at “rhythm” in English translations of the Qurʾan really so doomed to failure as Pickthall suggests? Is there something about the English language that makes it especially ill-suited to rhyming translation? Or are Pickthall and the others simply being obtuse or myopic?

* Devin Stewart is Associate Professor of Arabic and Middle Eastern studies at Emory University.© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2015. All rights reserved.