IQSA San Diego Program, 21-24 November 2014

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.

by Gabriel Said Reynolds*

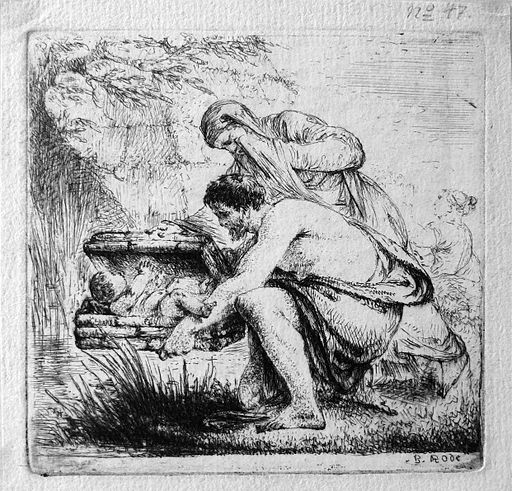

Moses Set Out on the Nile in a Reed Basket. Engraving by Bernhard Rode, ca. 1775; photo accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Qurʾan 20:39 recalls how God instructed Moses’ mother to place her infant son in a tābūt and set him upon a river, that he might escape Pharaoh. In Modern Standard Arabic, tābūt can mean “box, case, chest, coffer” or “casket, coffin, sarcophagus,” and many translators render tābūt in the Qur’an in light of one or another of these meanings. Asad (“chest”), Hilali-Khan (“a box or a case or a chest”), Yusuf Ali (“chest”), Hamidullah (“coffret”), and Paret (“Kasten”) all choose the first meaning; Quli Qaraʾi (“casket”) chooses the second.

The awkward image of the infant Moses floating on the Nile in a casket illustrates the problem of understanding Qurʾanic terms in light of their meanings in Modern Standard Arabic. Not all translators do so. Pickthall and Arberry, among others, render tābūt, “ark.” This dramatically different translation presumably reflects the influence of Qurʾan 2:248, where the Qurʾan uses tābūt for the Ark of the Covenant.

In fact, Q 2:248 is the key to understanding tābūt in Q 20:39. Tābūt reflects the Hebrew term tebā (itself a borrowing from Egyptian), the term used for the basket in which Moses’ mother places him (Exodus 2:3; tebā evidently means “basket” here because it is made  out of reeds). Tebā is also used for the ark that Noah builds (Genesis 6:14, 15, passim). As Arthur Jeffery (Foreign Vocabulary, 88-89) notes, Qurʾanic tābūt is closer in form to Aramaic tībū (used in Targum Onkelos for both Noah’s ark and Moses’ basket) and even more so to Ethiopic tābot. The connection with Ethiopic tābot might be particularly important since it (like Syriac qebūtā) is used for Noah’s ark, Moses’ basket, and the Ark of the Covenant.

out of reeds). Tebā is also used for the ark that Noah builds (Genesis 6:14, 15, passim). As Arthur Jeffery (Foreign Vocabulary, 88-89) notes, Qurʾanic tābūt is closer in form to Aramaic tībū (used in Targum Onkelos for both Noah’s ark and Moses’ basket) and even more so to Ethiopic tābot. The connection with Ethiopic tābot might be particularly important since it (like Syriac qebūtā) is used for Noah’s ark, Moses’ basket, and the Ark of the Covenant.

In any case, my point here is not to make an argument about a particular etymology for tābūt but rather to illustrate the danger of relying on Modern Standard Arabic in our reading of the Qurʾan. The way in which the Qurʾan uses tābūt for both Moses’ basket (Q 20:39) and the Ark of the Covenant (Q 2:248) reflects the Biblical background of this term. Therefore, in Qurʾan 20:39, tābūt might be understood in light of this background to mean simply “basket” (even if this meaning is not found in Hans Wehr’s dictionary).

Tābūt is not the only example of the problem of Modern Standard Arabic understandings of the Qurʾan. Qur’an 3:44 alludes to the account of the contest between the widowers of Israel over Mary. In the version of this account in the (2nd century) Protoevangelium of James, all of the widows hand their staffs (as lots) to the priest Zechariah, in whose care Mary has been kept in the Jerusalem Temple. From the last staff, that of Joseph, a dove emerges, indicating that he is God’s choice. The term that the Qurʾan uses for these staffs is qalam (pl. aqlām), from Greek kalamos (“reed”). Yet qalam also came to mean “pen,” and indeed this is its common meaning in Modern Standard Arabic. Thus if one reads the Qurʾan in light of Modern Standard Arabic, Q 3:44 would seem to involve throwing pens around.

A final case, the term dīn, has theological consequences. As Mun’im Sirry points out in his recent work Scriptural Polemics: The Qurʾan and Other Religions (esp. 66-89), many modern commentators understand Qurʾanic occurrences of dīn to denote “religion,” and indeed translators almost always render dīn “religion” (for Q 3:19 I did not find any cases where it is translated otherwise). This has important consequences, especially with verses such as Q 3:19 and 85, which can be read to mean that Islam is the only acceptable religion. Yet in light of Semitic and non-Semitic cognates (such as Syriac dīnā), Qurʾanic dīn might have—in some instances at least—a more general meaning of “judgment” (hence the phrase yawm al-dīn). In other instances, dīn might mean something closer to religious disposition, rather than religion in the modern sense of a communal system of faith and worship. Accordingly, students of the Qurʾan should be wary of reading dīn, or any Qurʾanic term, through the lens of Modern Standard Arabic.

The International Qur’anic Studies Association welcomes paper proposals from all graduate students and scholars for its upcoming meeting in San Diego, CA, November 21-24. Submissions can be made under any of the five program units, listed here. Important guidelines regarding submission can be found below, as well as on the Annual Meeting page.

This week, we highlight the program unit titled “The Qur’an and the Biblical Tradition,“ chaired by Cornelia Horn and Holger Zellentin.

The focus of this unit, which will also host two panels at the November conference, is the Qur’an’s relationship to the Biblical tradition in the broadest sense. Thus the program unit chairs seek papers that engage the books of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament in the various languages of their original composition and later translations (regardless of a particular book’s status of canonization within specific Jewish or Christian groups); the exegetical traditions of the Bible; and the homiletic, narrative, and legal corpora that have developed in close dialogue with this Biblical tradition prior to the emergence of the Qur’an and subsequently in exchange with the Qur’an.

The first panel will be co-sponsored by the SBL Syriac Literature and Interpretations of Sacred Texts section. For it, proposals are encouraged that engage the Qur’an’s dialogue with any aspect of the Biblical tradition. Examples of possible emphases include the role of Syriac homilies by authors such as Jacob of Serugh or Philoxenos of Mabbug and the role of the Ethiopic tradition.

For the second panel, proposals should address methodological questions pertinent to the study of the literary shape of the Qur’an─both on its own terms and in relation to other written and oral texts.

Proposals should include a title and an abstract of approximately 400 words. For further detail see here.

* IQSA is an independent learned society, although our meeting overlaps with those of SBL and AAR. In order to attend IQSA 2014, membership in IQSA and registration for the SBL/AAR conference will be necessary. (The first day of the IQSA conference, however, will be open to the general public).

* All interested students and scholars may submit a proposal through SBL’s website, here. Scroll down to the “Affiliate” section, then click on the chosen IQSA program unit name. [Look in particular for the “(IQSA)” indication at the end of the unit titles]. Instructions for those with and without SBL membership can be found by clicking through to these individual program unit pages.

* Details on low-cost membership in IQSA will be published on the IQSA blog in Spring 2014. Make sure you are subscribed!

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.