Seventh Mingana Symposium on Arab Christianity & Islam: “The Qur’an and Arab Christianity”

By David Bertaina

The Alphonse Mingana Manuscript Collection at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom holds an important yet underappreciated repository of early Qur’an folios and papyri. In support of the Mingana collection and its legacy, a number of scholars gathered on 17-20 September, 2013, to discuss the importance of “The Qur’an and Arab Christianity.”

Fifteen papers were delivered at the Seventh Mingana Symposium on Arab Christianity & Islam. Topics ranged from pre-Islamic Arabic to medieval approaches to the Qur’an. This post highlights some of the important contributions made to the textual history of the Qur’an by scholars at the conference. The papers revealed the range of Middle Eastern Christian attitudes toward the Qur’an, their role in its emergence and interpretation, and the text’s subsequent impact upon Christian Arabic literature.

Chronologically, the papers tended to fall within the following parameters as: 1) the emergence of the Qur’an; 2) Abbasid-era Christian Arabic responses to the Qur’an; and 3) Later medieval Arab Christian inculturation of the Qur’an.

In the earliest chronological period, Robert Hoyland presented his case for the existence of pre-Islamic Christian Arabic literature based upon an Arabic martyrion inscription dated to ca. 570, among several other examples, which has implications for the formation of the Qur’an and its possible references to Christian Arabic dialects and/or Syriac.

Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala presented a reconstruction of the story of the destruction of Sodom in the Qur’an. His paper argued that we can discover the “textual archaeology” of the Qur’an’s many references to Sodom by assembling them together. The result is that the Qur’an’s homily on the event, probably transmitted via oral or written interactions, suggests a pre-canonical Qur’anic version of the story that was complete and closer to Late Antique versions of the legend.

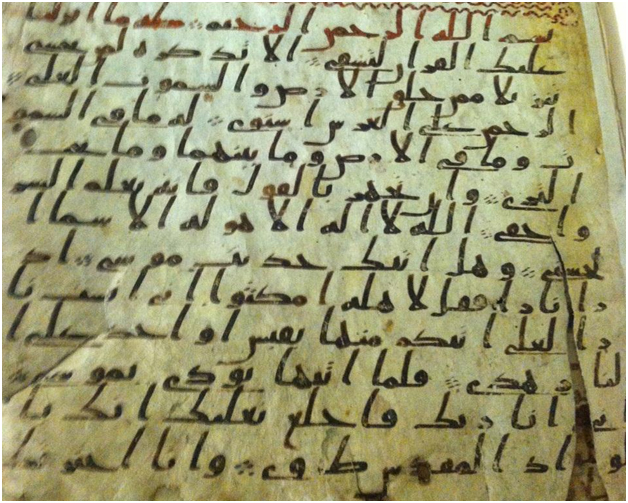

Alba Fedeli’s study examined a number of early Qur’an fragments from the Mingana Collection. The group was able to visit the repository at the University of Birmingham and inspect a number of these early fragments thanks to her preparations. In her presentation, Fedeli pointed out examples of textual emendation in early Qur’an texts that suggest a re-writing of texts to conform to later canonical versions of the holy text (see the bottom line of the pictured insert for an example). Moreover, her study of a Qur’an palimpsest in a Christian Arabic manuscript suggests the concept of linking early Islam with Arab Christianity needs further attention in the academy.

Krisztina Szilagyi examined Muslim and Arab Christian interpretations of Q 53:7-10 and Q 112 in reference to the fact that God is called al-ṣamad. She pointed out eight instances from Christian Arabic sources, ranging from the eighth century through eleventh century, that assume that early Muslims understood this word to associate corporealism with the divine. Szilagyi argued that corporealism might have been more prevalent than previously thought among the first Muslims and that these Christian critiques were one of the possible reasons for the decline of corporealism in Islamic theology.

Thomas Hoffmann argued that scholars need to escape textual assumptions about the Qur’an’s changeable attitude toward Christians. This position assumes Qur’anic theological unity and understands the text’s ambivalence toward Christians solely through historical contingencies and/or divine guidance. Hoffmann argues that scholars should approach the Qur’an not as a smoothed-out unified work but as a document of heterogeneous and competing positions.

Gabriel Said Reynolds presented on recent scholarly debates concerning the history of the Qur’an, arguing that many studies presuppose a later Islamic interpretive framework that potentially hinders our knowledge concerning the earliest stages of the formation of the Qur’an. Instead of presupposing a “normative” ʿUthmānic codex on which to judge early manuscripts, scholars need to read the texts while being open to surprising discoveries regarding its textual formation.

The second chronological period covered in the conference was Abbasid-era interactions concerning the Qur’an. Mark Beaumont discussed the ninth-century theologian ʿAmmār al-Baṣrī and his response to the Islamic critique of the Christian Scriptures. Beaumont argued that ʿAmmār al-Baṣrī was less concerned with philosophical categories inherited from the Greek tradition and was more focused on defending the logic of Christian theology as consistent with the presuppositions of Islamic thought based on the Qur’an.

Sandra Keating and Emilio Platti both presented on the Arab Christian author ʿAbd al-Masīḥ al-Kindī (ca. 825). His history of the collection of the Qur’an is one of the earliest accounts about the formation and collation of the text, even predating most Islamic hadith about the circumstances of its emergence. Purporting to be an exchange of letters between the Muslim al-Hashimī and the Christian al-Kindī, Keating and Platti explained how al-Kindī was deeply familiar with Islamic and independent sources regarding its origin and collection as well as the text itself.

Mike Kuhn explored the Muslim view of the Apostle Paul in the Abbasid period and how several authors employed the concept of taḥrīf to explain his role in the development of Christianity. Focusing on the Mu’tazilite ʻAbd al-Jabbār (d. 1025), he argued that his account of Paul’s life was a response to the analysis of the true religion by the ninth-century Syriac Church of the East member Hunayn ibn Isḥāq. Whereas Ibn Isḥāq argued that Christianity was not established by coercion, ʻAbd al-Jabbār claimed that Paul was motivated by political ambitions, which had implications for later Islamic polemics.

Gordon Nickel examined the impact of Q 7:157 on Muslim interaction with Arab Christianity. Since interpreters assumed this passage suggested Jews and Christians were expecting a prophet foretold in their Torah and Gospel, they had to explain why the communities failed to accept Islam. Nickel argued the Muslims began to claim verses in the Qur’an referred to the falsification of the earlier scriptures because Jews and Christians denied the existence of references to Muhammad in their holy books.

There were three papers on later medieval acculturation of the Qur’an in the Arab Christian milieu. David Bertaina presented on the concept of Qur’anic authority in the work of a Muslim convert to Coptic Christianity named Būluṣ ibn Rajāʾ (ca. 1000). He explained how Ibn Rajāʾ used the Qur’an in a positive sense arguing that his former co-religionists had failed to live up to its standards. Bertaina argued that his use of the Qur’an contrasted with other Arab Christian assessments of the Qur’an as a distorted Scripture.

Ayse Icoz examined the use of Qur’anic terms and phrases in the late tenth century Christian Arabic encyclopedia entitled Kitāb al-Majdal. Focusing on the particular examples from the text, Icoz argued that the form and the extent of the use of Qur’anic terms in Christian context reveal the author’s high acquaintance with Islamic vocabulary and deeper engagement with the surrounding culture.

David Thomas, the organizer of the conference, closed with an analysis of the use and abuse of the Qur’an in Paul of Antioch’s Letter to a Muslim Friend, composed in the thirteenth century. While some passages were quoted faithfully, Thomas argued that Paul’s misuse of the Qur’an suggests an established polemic in the Arab Christian repertoire and lessens the likelihood that the letter would have had a serious impact on its audience.

Many of these papers will be published with E. J. Brill under the History of Christian-Muslim Relations series edited by David Thomas. It will be a valuable addition to any scholarly collection or academic library. The conference will be held again in 2016 or 2017 in Birmingham, focusing on Christian-Muslim interactions in the earliest periods of encounter, and will once again be a lively place for the discussion of matter relevant to those who study the textual history of the Qur’an.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2013. All rights reserved.