The Qur’anic Manuscripts of the Mingana Collection and their Electronic Edition

By Alba Fedeli

1. Birmingham: Qur’anic Manuscripts in the Mingana Collection

Fifteen years ago my late mentor, Sergio Noja Noseda, showed me a few ancient Qur’anic parchments published by Giorgio Levi Della Vida in his 1947 catalogue. Those images were the starting point for Noja Noseda’s studies in Qur’anic manuscripts when he was a young scholar following the advice of Giovanni Galbiati (1881-1966), the prefect of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana. His story was the starting point of my studies in the same field. Subsequent movements from manuscript to manuscript led me to the University of Birmingham, England, where I am now based.

My research in Birmingham focuses on four early Qur’anic manuscripts of the Mingana collection, held in the Cadbury Research Library. The first fragment (MS Mingana Christian Arabic Additional 150) is a palimpsest that was hidden for many years by its scriptio superior and by being wrongly catalogued as an unknown Christian text.[1] Recently I identified its scriptio inferior as a portion of the Qur’anic text, perfectly fitting together with an incomplete half-folio of the famous Cambridge palimpsested codex, the so called Lewis-Mingana palimpsest (MS Cambridge University Library Or.1287). The second manuscript of the Birmingham collection is MS Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572, nine parchment leaves in two parts. One part fits together with MS Marcel 17 in St. Petersburg and MS MIA67 in the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, whereas the other part fits together with MS BnF ar. 328c in Paris. The third fragment (MS Mingana Islamic Arabic 1563) is composed of 39 parchment leaves. Finally, the Birmingham collection includes an uncatalogued papyri collection that Adolf Grohmann had inspected and recommended to a few German libraries, but due to difficulties in getting payment from Germany in the Thirties, the antiquarian Erik von Scherling of Leiden preferred to sell it to Mingana in Great Britain. Among these papyri, one fragment bears a small section of the Qur’anic text.

It is remarkable that all the fragments have the same provenance, in that after Alphonse Mingana had been appointed curator of the Selly Oak Colleges Library in Birmingham, he purchased from Erik von Scherling the papyri collection in 1934 and then—in May, September and October 1936—the above-mentioned Qur’anic fragments on parchment.[2]

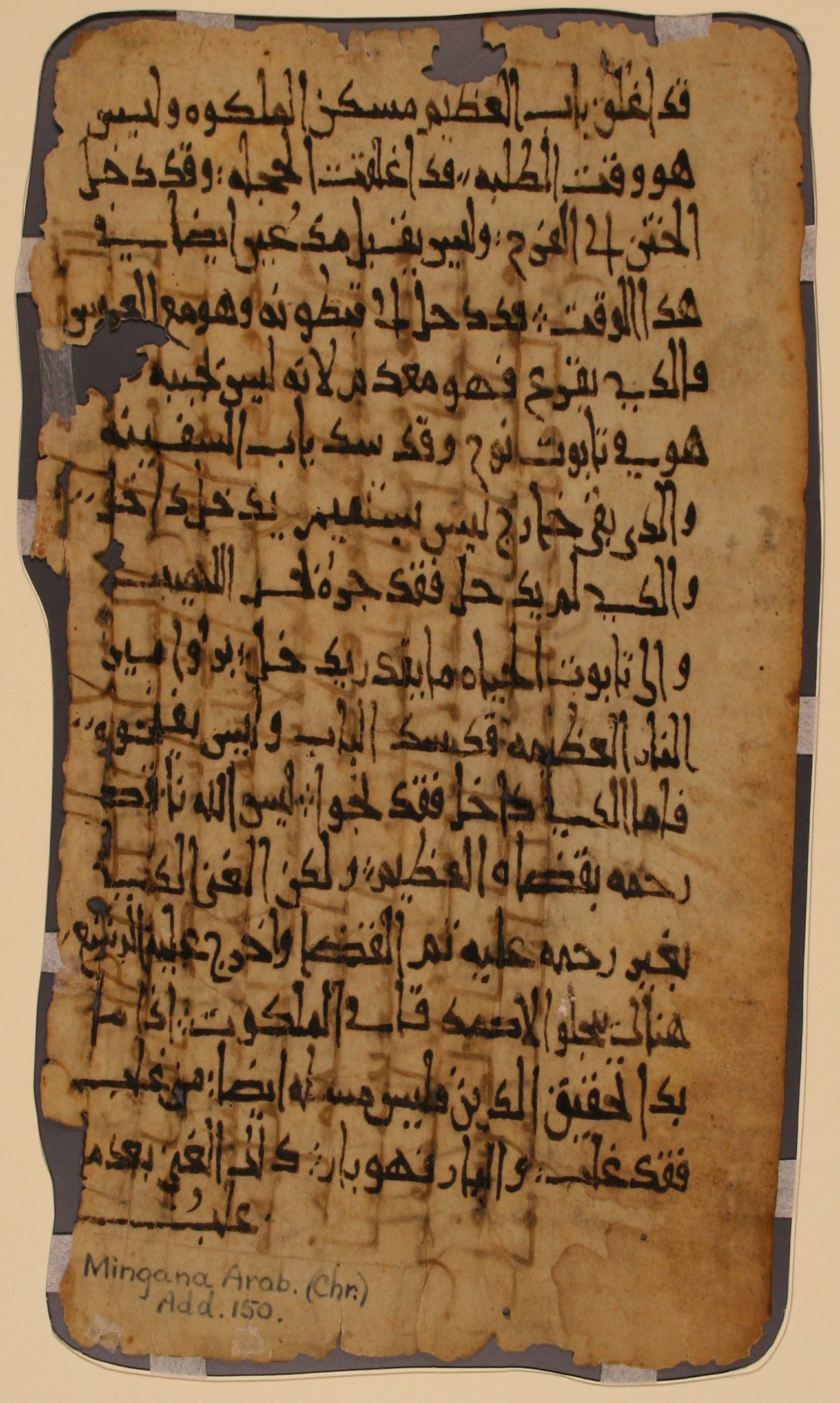

MS Christian Arabic Additional 150, recto. MS Christian Arabic Additional 150, rectoSpecial Collections, University of Birmingham by courtesy of Cadbury Research Library

2. Birmingham Qur’anic Manuscripts: Text, Contexts and Electronic Edition

First, my research on these Qur’anic fragments focuses on the comprehension of the linguistic characteristics they feature. Notably, a few deviations from the standard text found in the manuscripts reflect the linguistic competence of the scribes who were in charge of writing the text, and these linguistic features appear similar to the linguistic characteristics of early papyri. Secondly, the research explores the manuscript text by comparing it with the literature of the Islamic tradition, in order to comprehend the qirā’āt tradition as it is reflected in early Qur’anic manuscripts.

In addition, my research focuses on Alphonse Mingana’s papers held in the Cadbury Research Library, in seeking to place these manuscripts in their historical context. The papers give important information about the provenance of the manuscripts themselves,[3] as well as interesting information about scholars beyond the official story of their published works–thus depicting the atmosphere of Qur’anic studies in the ’30’s.

The outcome of the study of Birmingham early Qur’anic fragments will be their electronic edition. Indeed, my work adopts the approach of digital philology in editing and tagging the manuscript texts, so that the text may be converted to XML, thus transferring the rich manuscript evidence to the web. I am doing this work thanks to the support of the Institute of Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing in Birmingham, whose scholars have extensive experience in the field of electronic editions—such as, for example, the Codex Sinaiticus Project.

This electronic edition will be not only an expedient way to exhibit the edition and the analysis of the manuscript text but it will also affect our access to it. The digital tools offer technological solutions suitable for representing the movements of the text and its stratigraphic layers, working contrary to the idea of a fixed edited text. Thus an electronic edition and digital philology represent a different approach to the manuscript text itself.

3. The Tools: Non-linear Editions of Stratigraphic Records in Reproducing Textual Images

The use of digital editions and digital tools in editing codices that are now scattered in various institutions—like the Birmingham-Cambridge or the Birmingham-Doha-St. Petersburg fragments—offers two distinct advantages: first, the possibility of a virtual reunification of the codices and second, the prospects of reconstructing each of the two layers of palimpsested fragments.

In addition to this ideal presentation of a virtual/digital reality, digital editions permit a non-linear edition of stratigraphic records. These Qur’anic fragments are stratigraphic records of information added at different stages. The digital edition perfectly renders their multi-layered nature, taking the reader beyond the limits of the linear printed edition. Early Qur’anic fragments are, in some cases, the results of a settlement of differences, a compromise between two (or three) different systems. In different historical moments the two systems could have been coexisting or competing. The manuscripts express a mélange, a compromise between two systems. The manuscripts’ text is a dynamic text and it has a variant nature. Here I am referring first to the stages of the writing process, in that manuscripts could be a mélange of three systems (coexisting and competing); and second to the coexistence of alternative readings marked by red dots (whereas there is no coexistence of alternative readings marked by diacritical signs), as well as to the competition between two alternative readings.

As regards the first mélange, the different stages of the writing process are marked in these manuscripts using different ink colors, i.e. brown, red and black inks. In the electronic edition, the stages can be edited using the appropriate tags. Thus tags for first hand writing, second and third copyists/correctors, etc., offer the possibility of a stratigraphic transcription of the manuscript text, in contrast to the linear printed edition.

Furthermore, with reference to the second mélange, electronic editions offer the possibility of transcribing the coexistence and the competition of two different systems and the possible correction in the case of a competition that leads to the suppression of one of the two systems. The appropriate tags of alternative readings and the “corrector tags” attached to one of the two alternative readings offer the possibility of editing the information marked in the script. This means that the electronic edition contains all of the information from the stratigraphic records, so that the edition can later answer specific research questions through the established database.

4. The Manuscript Text: Using Digital Tools and Electronic Editions Means a Different Approach

Thus the digital edition of the Birmingham early Qur’anic fragments results in representing the systems performed in the manuscript text. In fact, if the image of a text (i.e. its transcription) can be viewed as a linguistic structure that represents a system,[4] these ancient Qur’anic manuscripts are particular expressions of the presence of more than one system. Thus the strategies adopted in transcribing the image of the text of the manuscripts and their systems are based on the digital philology tools. The starting point of these strategies chosen in editing and tagging the manuscript texts and the manuscript characteristics—like the above-mentioned tags of first hand and second copyist, as well as of alternative reading—are the guidelines gathered by the Institute of Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing and the manual of David Parker.[5] ITSEE’s Guidelines is a manual specifically pertaining to the transcription of Greek manuscripts, within the International Greek New Testament Project, and we have adapted these Guidelines to the characteristics of the early Arabic manuscripts of the Birmingham collection.

Finally, digital tools are not only tools for rendering in a non-linear edition the systems performed and added at different stages, but they also affect the methodology employed in editing the texts. In fact, the approach to early Qur’anic manuscripts prescribed by the characteristics of digital philology could be important in the field of Qur’anic studies, in that we are presenting the text as a series of manuscript artifacts[6] or, more precisely, as a process.[7] Given the fact that the variants and the characteristics featured in the manuscripts are presented as textual movements, the presumption is that we are considering the text as a process. The Islamic qirā’āt tradition itself has described the history and the transmission of the written text as a process, depicting the variety of the text; whereas early Qur’anic manuscripts reflect this variety, for example, in two coexistent readings.

Coexistence of alternative readings marked by red dots (’an ’asri and ’an-i-sri) in Q.26:52

This is the image of the manuscript text we are exhibiting in the electronic edition of the Birmingham early fragments. The importance of digital philology lies in the change of perspective that will help us to understand the richness of the manuscript texts, without imposing the limiting idea of a critical edition of the Qur’anic text.

[1] The fragment was hidden by a wrong label from 1939 to 2011, i.e. from the publication of the manuscript’s catalogue until its discovery in 2011. In fact it is highly probable that Mingana was aware of the content of the scriptio inferior of the palimpsested fragment, as we can infer from his correspondence about a few experiments he conducted in 1937 in order to obtain photographs of the palimpsest, applying ultraviolet lights.

[2] The details of the provenance of the early Qur’anic fragments of Birmingham were mentioned in Alba Fedeli, “The provenance of the manuscript Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572: dispersed folios from a few Qur’anic quires,” Manuscripta Orientalia, 17, 1 (2011), pp. 45-56.

[3] See the information about the Sinai provenance of MS Mingana Christian Arabic Additional 150 in Alba Fedeli, “The Digitization project of the Qur’anic Palimpsest, MS Cambridge University Library Or. 1287, and the Verification of the Mingana-Lewis Edition: ‘Where is Salām?’”, Journal of Islamic Manuscripts, 2, 1 (2011), pp. 100-117.

[4] Cesare Segre, Semiotica filologica. Testo e modelli culturali. Torino: Giulio Einaudi editore, 1979, pp. 64-65.

[5] David C. Parker. An Introduction to the New Testament Manuscripts and their Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[6] Peter M.W. Robinson. “Manuscript Politics,” in Chernaik, W., Davis, C. and Deegan, M. (eds.), The Politics of the Electronic Text. Oxford: Office for Humanities Communication, 1993, pp. 9-15.

[7] “Every written work is a process and not an object” is the dictum proposed by D.C. Parker in his Textual Scholarship and the Making of the New Testament, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2012.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2013. All rights reserved.