An Apocalyptic Reading of Qur’an 17:1-8

By Mehdy Shaddel*

Modern scholarship on the Qur’an has, since long, pointed out three problems with the  traditional interpretation of Q Isrāʾ 17:1 as a scriptural testimonium for Muḥammad’s ‘ascension’ story. The first is that there is nothing in the verse, and not even in the whole pericope, to suggest that the ‘servant’ (ʿabd) mentioned therein must be identified with Muḥammad – although there is nothing against this identification either.[i] Secondly, the verse does not even allude to an ascension; it only speaks of a ‘nocturnal journey’ (isrāʾ).[ii] The third, and most worrying, problem of the ‘miʿrāj verse’ is in its seeming incongruity with the rest of the pericope. This apparent incongruity is so obvious that it has led some scholars to propose that the verse has been interpolated into the text in an attempt to produce a prooftext for Muḥammad’s ascension story.[iii] However, this has been shown to be untenable because of the textual cross-references between the verse and the rest of the pericope.[iv]

traditional interpretation of Q Isrāʾ 17:1 as a scriptural testimonium for Muḥammad’s ‘ascension’ story. The first is that there is nothing in the verse, and not even in the whole pericope, to suggest that the ‘servant’ (ʿabd) mentioned therein must be identified with Muḥammad – although there is nothing against this identification either.[i] Secondly, the verse does not even allude to an ascension; it only speaks of a ‘nocturnal journey’ (isrāʾ).[ii] The third, and most worrying, problem of the ‘miʿrāj verse’ is in its seeming incongruity with the rest of the pericope. This apparent incongruity is so obvious that it has led some scholars to propose that the verse has been interpolated into the text in an attempt to produce a prooftext for Muḥammad’s ascension story.[iii] However, this has been shown to be untenable because of the textual cross-references between the verse and the rest of the pericope.[iv]

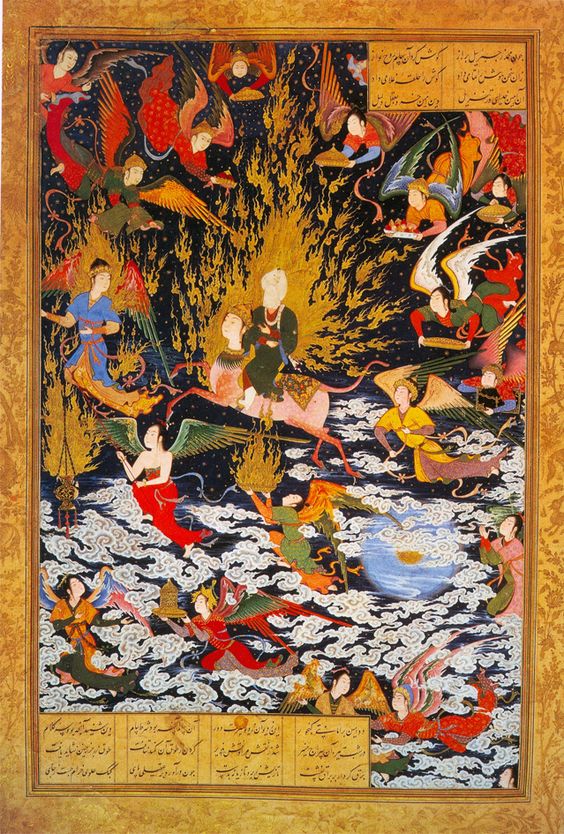

Apparently under the influence of the view that the verse stands out from the rest of the sūrah, almost no scholar has so far attempted to read Q 17:1 against the verses immediately following it (vv. 2-8) or vice versa. Some scholars, nevertheless, have granted that v. 1 may be a reference to a miraculous experience of its ʿabd (who they take the liberty of identifying with Muḥammad).[v] Such a miraculous journey, as Uri Rubin observes, is well-known in the Judaeo-Christian apocalyptic tradition.

On the other hand, vv. 4-7 retail a familiar story. It is the account of the destruction of the First Temple in Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylonian invasion of the Kingdom of Judah and the final destruction of the rebuilt Temple by the Romans in 70 CE, two cataclysmic events that for centuries continued to hold sway over the imaginaire of the Jews.[vi] These two events were, accordingly, retold, in the guise of ‘prophecies’, in many Jewish, and occasionally also Christian, apocalypses from the late first century CE onwards.[vii] One wonders, then, whether Q 17:1-8 is not a retelling of one such apocalypse, with v. 1 (the so-called ‘miʿrāj verse’) being the description of its seer’s initiatory experience?

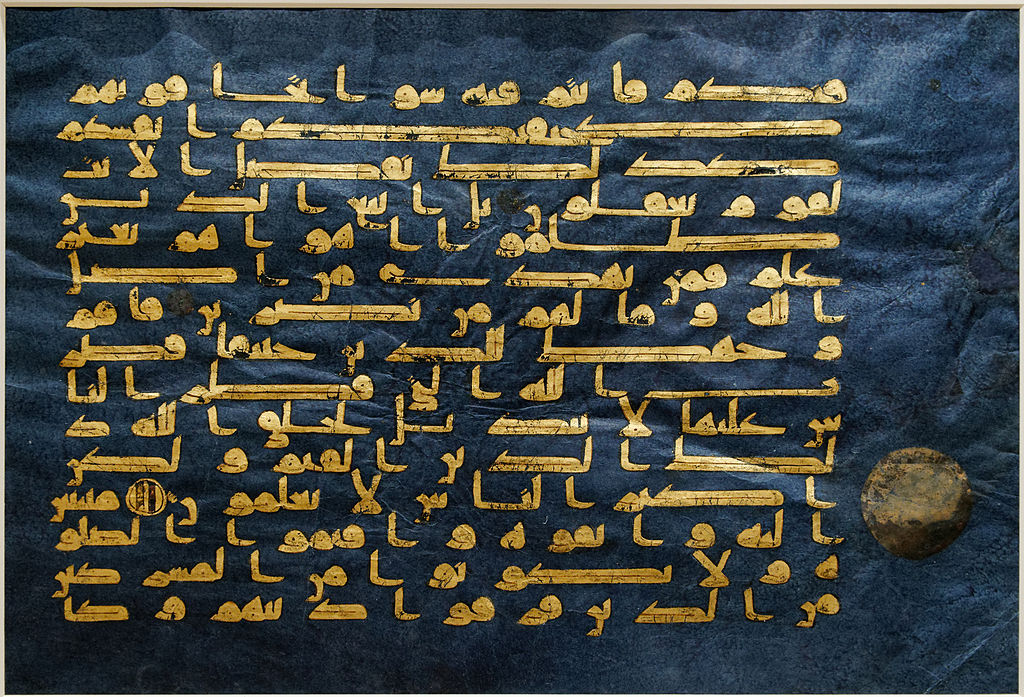

What is more, there could be little doubt that in v. 4 the Qur’an is alluding to an apocalypse. The verse asserts that God had beforehand determined those events to happen “in the book”.[viii] In other words, the Qur’an here is speaking of a book containing ‘prophecies’ of events – historical events – to come. This kind of already-fulfilled (or ex eventu) ‘prophecies’ are amply found in apocalyptic writings.

The possibility that the Qur’an might exhibit knowledge of apocryphal literature and, in particular, apocalypses is almost indisputable. Elsewhere in the Qur’an, we hear of ṣuḥuf (sing.ṣaḥīfah), a term used to describe “ancient compositions” (al-ṣuḥuf al-ūlā) attributed to Abraham and Moses, which, in all likelihood, is an Arabic calque on the Hebrew gilāyōn and the Syriac gelyānā, ‘scroll, apocalypse’.[ix] More to the point, emphasis on the role of divine providence in the unfolding of history is part and parcel of apocalyptic historiography. In apocalyptic historiography, the providential determination of history is to be seen in the phenomenon of translatio imperii according to a preconceived divinely-ordained scheme which, however, is usually said to be a chastisement for human sinfulness – presumably to shed any possible doubts as to the justness of the Almighty.[x] The same themes are evidently present in the qur’anic passage under discussion: a supra-historical view of the Israelite past and future that sees both God’s hand and human action behind all of their turns of fortune. The Qur’an, however, does not deploy this theology of history to convince its audience of the imminence of the eschaton or the inevitability of human suffering, but, rather, of the quickness of divine retribution. Thus the pericope seems to exhibit all formal features of the genre ‘apocalypse’.[xi]

Open questions

Scholars have identified two pseudepigraphic compositions as the apocalypse behind this pericope, the Apocalypse of Abraham, proposed by Geneviève Gobillot,[xii] and Testamentum Mosis (also known as Assumptio Mosis), put forward by Heribert Busse. Of these two, the Apocalypse of Abraham does contain a reference to the Roman sack of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, but it could hardly be “the book” cited by our pericope, for the allusion to “the book granted to Moses” in v. 2, which is presumably the referent of “the book” of v. 4, renders Abraham an impossible candidate for the ʿabd of v. 1.

Busse fails to connect v. 1 with the rest of the pericope himself and, thus, does not identify its ʿabd with the apocalyptic visionary. But, in the light of the foregoing, the identification of theTestamentum Mosis as the apocalyptic composition quoted here by the Qur’an entails that Moses is the to be identified with the ʿabd. This, however, cannot be maintained either, for although theTestamentum contains references to two desecrations of the Temple, its visionary does not embark on an otherworldly journey. Moreover, Moses’ association with al-masjid al-ḥarām, wherever it was, is not self-evident in the light of the qur’anic data. On the other hand, Abraham seems a suitable candidate in this respect, as, contrary to Moses, he is particularly associated with al-masjid al-ḥarām in the Qur’an and is even said to be its founder. As may be seen, there is evidence for and against both candidates in the text, and, thus, the issue remains open.

What about the location of the two mosques mentioned? Van Ess, Neuwirth, and Rubin have compellingly argued for the identification of al-masjid al-aqṣā with the Jerusalem Temple on the basis of the verse’s description of it as being contained in a blessed environment, a description used elsewhere in the Qur’an of the Holy Land.[xiii] The identity of al-masjid al-ḥarām still remains elusive, but it would not be hard to imagine that the Qur’an is indeed referring to its messenger’s hometown here, in keeping with its project of nativising biblical Heilsgeschichte.[xiv]

* Mehdy Shaddel is a scholar of Islamic history specialising in the political history of the early caliphate (AD 632-836), the Arabic historiographical tradition, the historical Muḥammad, the Qurʾān, and late-ancient religion. He has written several articles on such topics as the Second Muslim Civil War, ethno-religious identities in the Qur’an, and Islamic eschatology.

[i] Josef Horovitz, “Muhammeds Himmelfahrt”, Der Islam 9 (1919), 159-183, at 160; A.A. Bevan, “Mohammed’s Ascension to Heaven”, in Karl Marti (ed.), Studien zur semitischen Philologie und Religionsgeschichte: Julius Wellhausen zum Siebzigsten Geburtstag (Giessen: Alfred Töpelmann, 1914), 51-61, at 54; followed by John Wansbrough, Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation (Amherst: Prometheus, 2004), 67-9, who sees a better candidate in Moses, apparently in the context of the exodus of the Israelites (adducing, inter alia, Q al-Dukhān 44:23 as a potential parallel).

[ii] For the significance of this term, see Rubin, “Muḥammad’s Night Journey (isrāʾ) to al-Masjid al-Aqṣā: Aspects of the Earliest Origins of the Islamic Sanctity of Jerusalem”, al-Qantara 29 (2008), 151.

[iii] Theodor Nöldeke and Friedrich Schwally, Geschichte des Qorāns, vol. i: Über den Ursprung des Qorāns (Leipzig: Weicher, 1909), 136 (translated into English as The History of the Qurʾān. ed. and trans. Wolfgang Behn [Leiden: Brill, 2013], 111-2); Horovitz, “Muhammeds Himmelfahrt”, 160; more explicitly so in Bevan, “Mohammed’s Ascension”, 53; more recently in Angelika Neuwirth,Studien zur Komposition der mekkanischen Suren (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2007; originally published in 1981), 101, based on stylistic grounds. Neuwirth has since backtracked on her earlier position by contriving a redactional history of the verse in the context of the whole sūrah which integrates it back into the original corpus of the Qur’an; see her “From the Sacred Mosque to the Remote Temple: Sūrat al-Isrāʾ (Q. 17), between Text and Commentary”, in eadem, Scripture, Poetry and the Making of a Community: Reading the Qur’an as a Literary Text (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 216-52, at 225-7 (originally published in J.D. McAuliffe, B. Walfish, and J. Goering [eds], With Reverence for the Word: Medieval Scriptural Exegesis in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003], 376-407).

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Rubin, “Muḥammad’s Night Journey”, 152-3; Neuwirth, “From the Sacred Mosque”, passim.

[vi] This identification, which is also advocated by the tradition, has been challenged by Busse, “Destruction of the Temple”, 2-3, on the basis of his own identification of Testamentum Mosis as the ‘source’ of the verse.

[vii] Many such texts are discussed in Kenneth R. Jones, Jewish Reactions to the Destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70: Apocalypses and Related Pseudepigrapha (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

[viii] Cf. Busse, “Destruction of the Temple”, 3, who suggests the Testamentum Mosis as a likely candidate.

[ix] Q al-Aʿlā 87:18-9; al-Najm 53:36-7; and Ṭāhā 20:133. Haggai Ben-Shammai, “Ṣuḥuf in the Qurʾān – A Loan Translation for ‘Apocalypses’”, in idem, S. Shaked, and S. Stroumsa (eds), Exchange and Transmission across Cultural Boundaries: Philosophy, Mysticism and Science in the Mediterranean World (Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2013), 1-15.

[x] On the function of ex eventu prophecies in apocalyptic literature, see Christopher Rowland, The Open Heaven: A Study of Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity (London 1982), 136-55; andnow Lorenzo DiTommaso, “Pseudonymity and the Revelation of John”, in J. Ashton (ed.), Revealed Wisdom: Studies in Apocalyptic in Honour of Christopher Rowland (Leiden 2014), 305-315.

[xi] The classic definition of the genre is to be found in John J. Collins, “Introduction: Towards the Morphology of a Genre”, in idem (ed.), Apocalypse: The Morphology of a Genre (special issue ofSemeia 14 [1979]), 1-20.

[xii] Geneviève Gobillot, “Apocryphes de l’Ancien et du Nouveau Testament”, in Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi (ed.), Dictionnaire du Coran (Paris: Bouquins, 2007), 57-63.

[xiii] Josef van Ess, “Vision and Ascension: Sūrat al-Najm and Its Relationship with Muḥammad’s miʿrāj”, Journal of Qur’anic Studies 1 (1999), 47-62, at 48; Rubin, “Muḥammad’s Night Journey”, 152; also alluded to in Neuwirth, “From the Sacred Mosque”, 225 and 234.

[xiv] For further examples of the Qur’an’s appropriation of Judaeo-Christian folk stories and their situation in an ‘Arabian’ milieu, see Joseph Witztum, “The Foundation of the House (Q 2:127)”,BSOAS 72 (2009), 25-40; and Mehdy Shaddel, “Studia onomastica coranica: al-raqīm, caput Nabataeae”, forthcoming in Journal of Semitic Studies 62 (2017).