Ritual Studies and the Qur’an: Preliminary Thoughts

by Andrew C. Smith*

The usage of ritual as a means of communication, worship, and social construction is a ubiquitous element in human societies. In recognition of this fact, the field of ritual studies has expanded in scope and relevance in the last half century. Yet ritual as an important element within the Qur’an is largely unstudied. This post offers preliminary thoughts on the application of theories and perspectives in ritual studies to the study of the Qur’an.

The study of ritual within the western academy has developed somewhat in tandem with religious studies, with Myth-and-Ritual, sociological, psychoanalytical, and structuralist schools of thought developing distinct approaches to the study of religious ritual. Since the mid-1960s, ritual studies scholars have come to value more interdisciplinary approaches, and to integrate many different fields—such as sociology, anthropology, religious studies, and cultural studies—into the study of ritual. Some of the most prominent thinkers on ritual in the last few decades include Catherine Bell, Ronald Grimes, Mary Douglas, Roy Rappaport, and Clifford Geertz. Their ideas, methods, and tools for studying ritual should form the basis for any study of ritual within the Qur’an.

For many years, ritual theorists have wrangled over a precise definition of “ritual,” but it is difficult to define because ritual as a category involves human emotions that are subjective and transient, and sometimes defy lingual expression (Muir, 2005, 2). It is also important to recognize that a universal, succinct definition may not only be impossible but also theoretically detrimental to the scholarly study of ritual (Bell, 2009, 82). For this reason, among others, many theorists have moved away from the utilization of strict definitions, preferring to devise more flexible typologies for describing, comparing, and analyzing ritual actions. Some scholars, like Grimes and Bell, go further to simply describe aspects of each ritual as “family characteristics” on a sliding scale of characteristics to determine if something is more or less ritualized. The strengths and weaknesses of these various approaches should be carefully weighed when considering which tools and methods will best fit the analysis of ritual action within the Qur’an.

Ritual as a category is most often studied contemporaneously with its performance, whereby an anthropologist or ethnographer views or participates in a ritual and queries the performers as to its meaning and function. And yet, much of the basis for religious ritual performance is found in written texts like the Qur’an. However, depictions of rituals in the texts may differ from their lived performances. For this reason we must differentiate between the study of ritual in Islam and the study of ritual in the Qur’an.

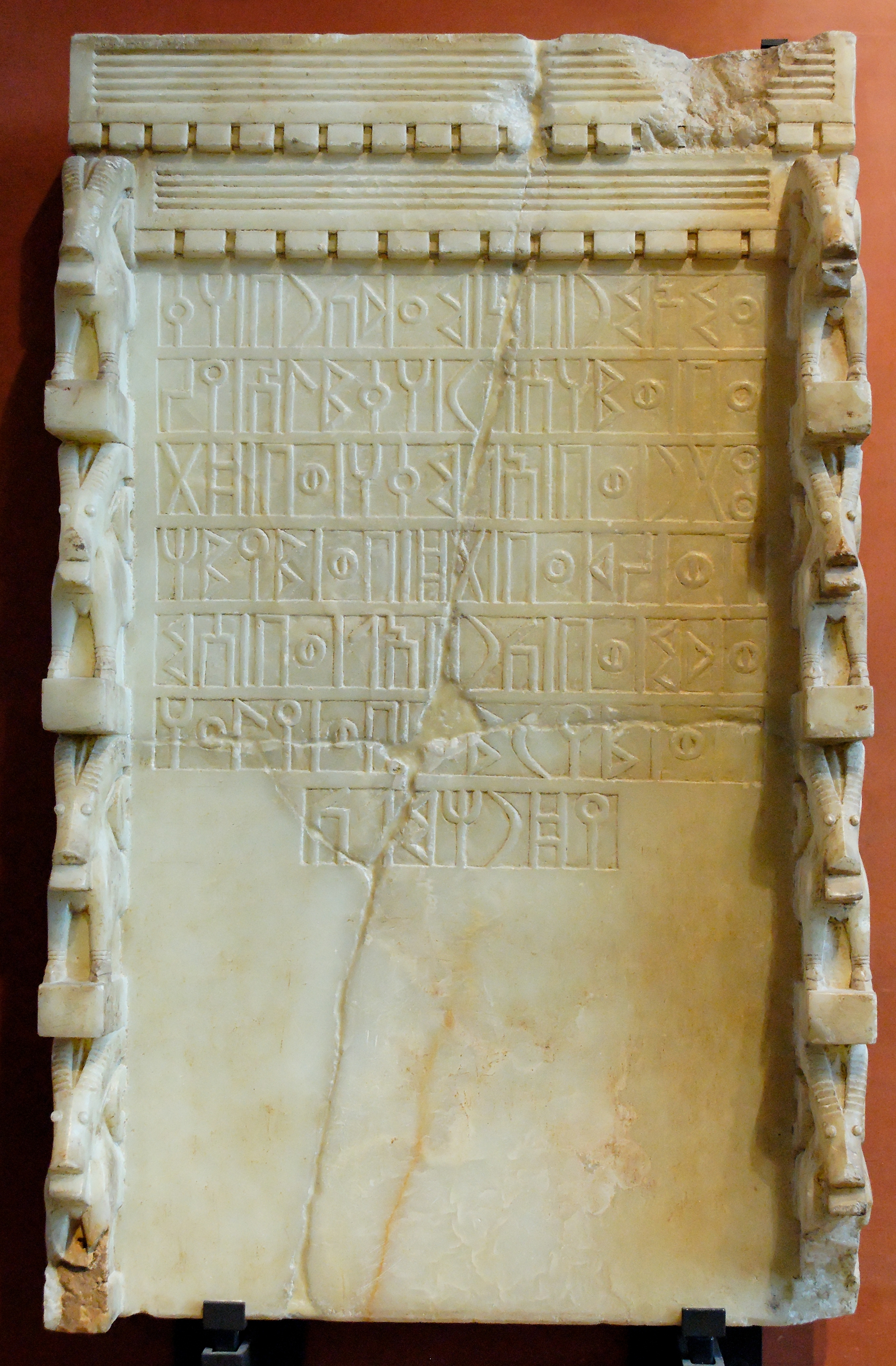

The idea that Muslims’ performing rituals in the present can shed light on how and why such rituals were performed at the time of the reception of the Qur’an is an assumption that needs to be treated carefully if not outright avoided. Ritual in the Qur’an must be primarily analyzed in its late antique historical context, which is significantly different from later contexts of Islamic ritual. We must consider the rituals contained in the Qur’an in connection with the religious communities of Late Antiquity, not through a lens of origin studies, but in order to understand the concepts of ritual usage that existed at the time, and the ritual symbolism and action from which they were adopted and adapted. For this purpose, research on the historical context and biblical subtext of the Qur’an—like that of Gabriel Said Reynolds and others—is vastly important.

The study of ritual as represented in the Qur’an is necessarily different from the study of ritual as a lived tradition. Researchers on the Qur’an cannot query a ritual’s late antique performers as to its purpose or meaning. They must rely solely upon the written text. At the same time, it must be remembered that written reference to ritual does not constitute ritual itself. Scholars relying on written evidence must also deal with some of the issues that more generally problematize the literary study of ancient texts, including questions of provenance and preservation, as well as the likelihood that a text may not have all the information that one would expect or wish to be present, due to editorial redaction, genre and form, or authorial intent.

To help overcome these and other challenges in studying ritual within the Qur’an, one can look to ritual studies as applied to the text of the Bible, including the works of Gerald A. Klingbeil, Mark McVann, Frank H. Gorman, David P.Wright, and Ithamar Gruenwald. Some of the issues identified within the study of biblical ritual apply directly to the Qur’an, while others apply only tangentially or not at all based on the basic differences between the Bible and the Qur’an in terms of composition, canonical development, etc. For example, the compositional character of the Arabic Qur’an—namely, the usage of sajʿ (rhymed prose)—leads to a general lack of prescriptive ritual designations, because detailed instructions about how rituals are to be performed do not appear to fit well within that artistic style.

Ritual study of the Qur’an is a wide-open field, with great potential for shedding light on the ways that ritual was understood and used by the earliest community of Muhammad’s followers to express their devotion and worship and to declare, create, and maintain their religious and communal identity. The preliminary thoughts presented above barely begin to tap the potential for greater engagement with this area of research. They are meant to stimulate further thoughts and conversations about the role of ritual within the Qur’an and the discourse of the early community of Muhammad’s followers.

* Andrew C. Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Religion at Claremont Graduate University.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2015. All rights reserved.