The Traditions on the Composition of ‘Uthmān’s muṣḥaf.

By Viviane Comerro

Viviane Comerro is Professor of Islamic Studies at INALCO (Paris). This blog is a synopsis of its French book titled “Les traditions sur la composition du muṣḥaf de ‘Uthmān”, Orient-Institut Beirut, 2012

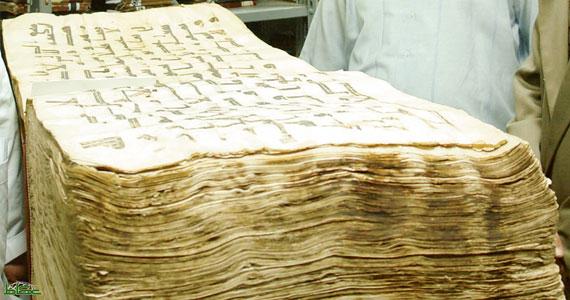

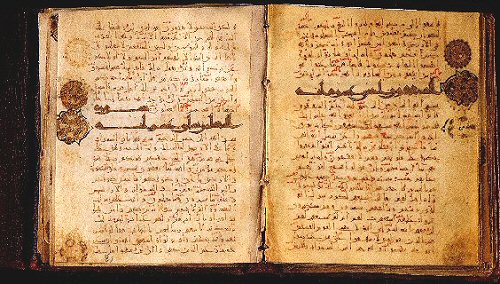

When and how did the Quran become a book? Even though paleography and codicology provide us with useful elements that shed light on this question, we should not overlook the study of Islamic literary sources which, through the diversity of their accounts on the writing of the Quran and the richness of their glosses on the Quranic text itself, remain bolder and more informed testimonies than any collection of manuscripts.

How should we address Islamic sources which provide us with numerous pieces of information on this issue? An initial historical approach based on the transmission of texts could lead us to follow the Ancients in their investigative endeavor by privileging the historical veracity of the version adopted by al-Bukhārī (d. 256/870) in his Ṣaḥīḥ.

A second, historical and critical approach has already achieved its full potential: drawing out a core that is common to the various versions of the account of the event so as to gain some certainty or extracting this historical core from its legendary, theological or ideological gangue.

Reflection upon the literary nature of sources that has developed alongside this approach has resulted in a transitory suspension of the “naively” historical approach. In fact, a tradition always provides the event and its interpretation as closely related. This is a khabar, information, as well as a hadith, an event set as an account. Thus, it is in taking into consideration the twofold nature of a tradition that I have read afresh the totality of the accounts on the writing of the Quran by paying very close attention to the variants and their meanings.

By placing back the received version of the event – the one Bukhārī kept in his Ṣaḥīh – in this totality, it appears as made up of several motifs that also exist in isolation as independent traditions. This version is therefore the result of a combination that selects some pieces of information while discarding others.

The author of this combination, or common link in the vernacular of the modern specialists of transmission, is Ibn Shihāb al-Zuhrī (d. 124/742), who certainly did not invent this story but combined different pieces of information on the writing of the Quran, as he did for other accounts.

Beyond this stage, the hadith of Zuhrī evolved even further since a version that is quite different from Bukhārī’s is to be found in the introduction to his Tafsīr by the great compiler of the 3rd century of Hegira, Ṭabarī (d. 310/923).

Apart from the issue of authenticity, wherever we place this version in the chain of transmission, what seems to matter is the reason why such a well-informed exegete as Tabarī chose this version of Zuhrī’s account rather than another one. This question led me to question Bukhārī’s stance and Ṭabarī’s regarding the status of Quranic recitation in the intellectual debates of their time. I came to the conclusion that, to some extent, the issue of the isnād was of secondary importance. What really matters is the content of each account.

For Ṭabarī, who claims that ‘Uthmān reduced the various recitations of the Quran to a single ḥarf in the official muṣḥaf, it is important to note that the Quranic text is not the result of a collection but the writing of a single man, Zayd b. Thābit.

For Bukhārī, it is important to take a stand in a critical debate of his time: that of the created or uncreated Quran, which goes on long after the end of the Miḥna by claiming that the writing of the Quran is created, in contrast with the Hanbali scholars.

Besides, the stance differs from one Ṣaḥīḥ to the other. Muslim (d. 261/875), Bukhārī’s contemporary, who frequented the same circles as him, apparently avoids to take a stand in this debate. Nowhere does he mention the account transmitted by al-Zuhrī. On the other hand, he mentions traditions on the various recitations of the Companions Ubayy, Ibn Mas‘ūd and Abū Mūsā. In this selection of information, one can detect a stand in another significant debate that lasted for centuries about the diversity of Quranic recitations theorized in the form of a prophetic hadith: Unzila l-qur’ān ‘alā sab‘ati ahruf. In this controversy, a stance became more and more a minority, yet it lasted for a long time: it was allowed to liturgically recite ancient qirā’āt, especially that of Ibn Mas‘ūd, due to the fact that the companions of the Prophet and the Successors did it, even though these “readings” were not in keeping with the ‘Uthmānian rasm. It seems that in the 3rd century, prior to Ibn Mujāhid’s reform, the traditionist Muslim was inclined to favor such a stance.

The discrepancies between the accounts about the writing of the Quran, which are already impressive regarding what comes from Zuhrī, are even more so when all the traditions are taken into consideration. They are so not only for the researcher who considers he should not side with the traditionists, now as in the past, but also because all these accounts excluded by the strict selection of the Ṣaḥīḥ reappear in the margin of a commentary or an argumentation by the early (or modern) authors among the most interested in orthodoxy.

Historical description is not the main goal of traditionists, who rather try to solve theological/juridical problems. The diversity of the accounts related to the writing of the Quran, which mostly took place under ‘Uthmān’s caliphate, could result from the traditionists’ worry about the composition of the muṣḥaf in an unfavorable historical context: a challenged caliphate in a time troubled by strong dissensions. The attested circulation of different maṣāḥif of the Quran, one of the sources of legitimacy and authority in the fullest sense of this dīn as the foundation of the new community, represented a danger for Medina’s power. After the historical situation changed, though it was never forgotten, the prime preoccupation concerned the conditions of transmission of the prophetic proclamation. The selection of the ḥarf of Zayd, a man related to ‘Uthmān, had not been consensual. And what to do with the maṣāḥif of Ubayy, Ibn Mas‘ūd, Abū Mūsā, Miqdād and others? Several responses to these unexpressed worries arose in the large corpus of narrative traditions on the writing of the Quran. I have suggested classifying these accounts according to the kind of solution they provided to ensure the faultless transmission of the muṣḥaf.

After this investigation in literary sources, it is to be noted that there is no received version of the writing of the muṣḥaf despite the status acquired by the Ṣaḥīḥ of Bukhārī and the repetition, book after book, century after century, of his hadith on the collection of the Quran, a “thing the Prophet had not done.” In this way, although a 12th century traditionist such as Abū Muḥammad Ḥusayn al-Baghawī reports Bukhārī’s account in his Sharḥ al-Sunna, in his commentary he carries out a rewriting of the event with the memory of other accounts. He claims that the composition of the muṣḥaf is an act involving the Companions as a collective actor of the ijmā‘: they are those who decided together with ‘Uthmān and those who wrote. This rewriting is as perceptible in the 15th century when al-Suyūṭī began his chapter of the Itqān devoted to the collection of the Quran by the blunt assertion that at the time of the Prophet’s death “the Quran had not been collected.” Throughout the text and in the conclusion of the chapter, it appears that the “thing the Prophet had not done” had in fact been accomplished since the muṣḥaf, organized as verses and suras, is exactly the same as that instituted by Muḥammad after the angel’s dictation.

In my book, I left the question of the writing of the Quran at the time of the Prophet open-ended owing to the scarcity of traditions that mention it. This question pertains to another kind of investigation on the oral/written composition of the Quranic text (Angelika Neuwirth) and could rest on the works of linguists and anthropologists dealing with orality and writing.

In conclusion, the study of traditions informs us on some crucial elements of the history of the text: the plasticity of its composition and oral transmission; the antiquity of its writing; the fixation of a model written under ‘Uthmān; its gradual canonization; the preservation of textual variants as a reflection of the original oral diversity and then the philologists’ interest; the parallel theologizing of the history of transmission.

Yet this study chiefly enables us to understand the Tradition that lends their full weight to the actors of transmission. Through selection, combination, additions or deletions, and when the text is permanently fixed in its letter, through their glosses, commentaries and interpretations, these actors contribute to the fluctuation in meaning in the preservation of religion.