“Fragmentation and Compilation” Workshop at the Institute for Ismaili Studies, London

By Holger Zellentin

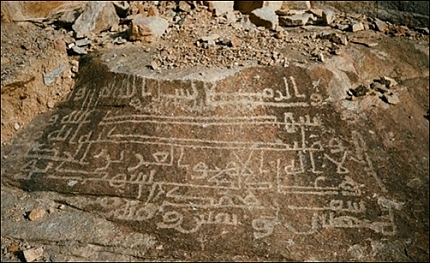

This past week, an exciting conversation took place at the Institute for Ismaili Studies in London. The event was convened by one of the Institute’s researchers, Dr. Asma Hilali, who brought together a broad range of researchers in Qur’anic studies. The workshop was the second installment in a series titled “Fragmentation and Compilation,” which seeks to explore the difficult conceptualization of partial transmission and re-arrangement of various “particles” relating to the Qur’an. Among the elements considered in terms of their fragmentation and subsequent compilation were sketches of individual Qur’anic verses and their arrangement within the Qur’an (and beyond), Qur’anic reading instructions and textual variants, and the role of Jewish literary frameworks and exegetical traditions in our understanding of the Qur’an. Presentations were given on material evidence such as: the Ṣan‘ā’ palimpsest (Asma Hilali), early Qur’anic graffiti from Arabia (Frédéric Imbert), the various voices used in Qur’anic discourse (Mehdi Azaiez), the Qur’an’s integration of Jewish exegetical topoi (Holger Zellentin), and on the compositional features of Tafsir collections (Stephen Burge).

The presenters’ initially distinct points of departure were united by more than their common focus on the text of the Qur’an. Aziz Al-Azmeh served as a brilliant and erudite discussant, probing the theses and turning the focus of the public discussion towards one overarching topic: the palpability of both unity and dynamism within the Qur’anic text, in its traditional form as well as in its various early iterations. The discussion among the presenters and the notable guests (such as François Déroche, Gerald Hawting, and Hermann Landolt) explored two topics in particular. The first constituted the possibilities and challenges inherent to integrating a study of Qur’anic manuscripts with a study of the Arabian Qur’anic graffitis from the first two centuries after the Hijra. Adjacent foci here were the dating of the earliest graffitis; the importance of the Parisino-Petropolitanus codex from Fusṭāṭ (Ms. Arabe 328); and the difficulties pertaining to the carbon-dating, the palaeography, and the reconstruction of the Ṣan‘ā’ 1 palimpsest. Secondly, the discussion repeatedly returned to the limits and imperatives of considering a basic chronology of the Qur’an, and the need to differentiate between the development of micro- and macroforms: i.e. between individual stories or traditions and the Surahs as a whole. A more objective way of establishing an inner Qur’anic chronology, it was suggested, is perhaps the increasingly precise tracing of the relatively pointed appearance of Syriac and Rabbinic literary form and content in specific Surahs.

More than a few doctoral theses are yet to be written covering even the most basic preliminaries connecting the material evidence of the text with its relationship to Late Antiquity. The conference was framed by a discussion of the state of the field of Qur’anic studies, and included a presentation of recent research projects housed in Berlin, Notre Dame, and Nottingham. Overall, the open atmosphere and spirit of respectful inquiry was a great success for the organizer and the hosting institution. Those who have missed the event will be able to read the proceedings in a publication edited by Dr. Hilali.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2013. All rights reserved.