King’s College Workshop Report: Patterns of Argumentation in Late Antique and Early Islamic Literature

By Barbara Roggema

On February 20-22, a workshop took place at King’s College London about patterns of argumentation in Late Antique and early Islamic literature. The workshop was organized by Yannis Papadogiannakis and Barbara Roggema within the framework of the ERC-project Defining Belief and Identities in the Eastern Mediterranean: The Role of Interreligious Debate and Interaction. This project seeks to recover the processes by which religious beliefs and identities were defined through interreligious interaction and debate in the religious culture of a broader social base in the eastern Mediterranean (sixth-eighth c. CE) through examination of a neglected, unconventional corpus of medieval Greek, Syriac, and Arabic literature of debate (consisting of collections of questions-and-answers, dialogues among others).

The papers covered a wide variety of source material: interreligious disputations, tafsīr, maghāzī literature, apologetics, gnomologies, erotapokriseis, chronicles, and early Islamic legal texts. The principal focus was on the ways in which religious ideas in the Eastern Mediterranean world were shaped by the challenges of rival religious groups, and especially, what patterns of argumentation were employed in these various types of literature in order to formulate answers to critical questions from inside and outside the community. At the same time, most papers addressed the more general question of the processes behind the transmission and transformation of ideas between the Late Antique Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities.

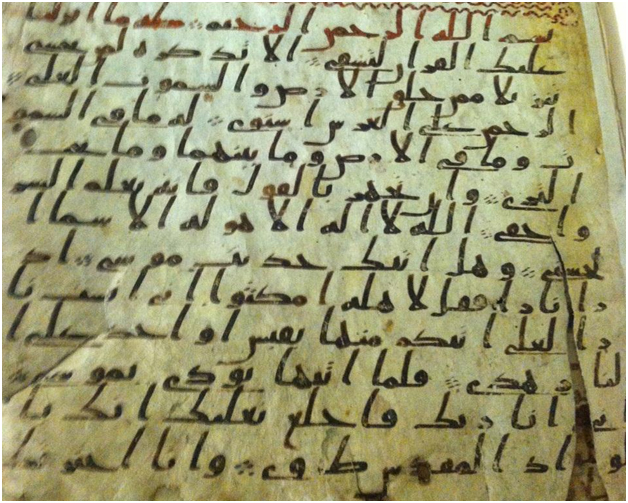

Fragment of a 9th century manuscript of the Arabic translation of the 7th/8th century Greek Quaestiones ad Antiochum ducem by Pseudo-Athanasius of Alexandria (Bibliothèque Nationale et Universitaire de Strasbourg, ms 4226).

With regard to Qur’anic Studies, several papers are relevant to mention here. David Bertaina’s “The Qurʾān as Question-and-Answer Literature: A Witness to Late Antique Disputation” focused on the strong connections between the Qur’an’s question-and-answer literary form and the culture of disputation in the Jewish and Christian milieu of the seventh century. He argued that the Qur’an records disputes in which its audience was engaged, but at the same time dissuades people from arguing over issues which pertain to the realm of Divine unknowability. One example is the reflection of disputes over the direction of prayer in Q 2:142. No answer is given to the heated question in this verse. Instead it diverts the issue to an evocation of God’s will, guidance and authority. Bertaina also discussed the possibility that the Qur’an preserves echoes of contemporary religious debates. An issue that might be reflected in Q 4:171, the verse in which the People of the Book are told not to say “three” about God, is the intra-Miaphysite dispute about John Philoponus’ tritheistic interpretation of Trinitarian theology.

Barbara Roggema’s paper dealt with post-Qur’anic Christian-Muslim confrontation. She discussed a Christian-Arabic papyrus, which was dated by Georg Graf to the middle of the eighth century and which contains polemical questions against the Qur’an. These critical questions feature in early tafsīr as well, but without being identified as polemical points made by Christians. Roggema argued that Arabic-speaking Christian critique of the Qur’an goes back at least to the eighth century, if not to the century before, and that it may have acted as a catalyst to the mufassirūn’s search for internal consistency in the Qur’an.

Michael Pregill’s paper “Making a Difference: Revelation, Prophetology, and the Shaping of tafsir in the ‘Sectarian Milieu’” also dealt with the impact of interreligious polemic on the formation of early Islamic tradition. He focused on the reshaping of Qur’anic narratives by early commentators, using the example of the Golden Calf narrative and the impact of the development of ideas about Biblical corruption (taḥrīf) and prophetic impeccability (ʿiṣma) on interpretation of the story.

How Islamic commentators reshaped Biblical narratives was also the topic of Marcel Poorthuis’s paper “Šekhinah and Sakīna or: on the rivalry between Moriah and Mecca.” Poorthuis showed how al-Ṭabarī, in his narration of Ibrahim’s founding of the Ka‘ba, used the non-Qur’anic term Sakīna to reflect the Jewish Šekhinah. He discussed how Jewish traditions were Islamicized when Isaac’s intended sacrifice on Mount Moriah was transformed into a genuinely Islamic story about the Sakīna and of the founding/discovery of the Ka’ba. This transformation entailed a change in understanding of the Sakīna, making it a jinn-like presence rather than an independent divine agent as in Jewish tradition.

This workshop will have a follow-up in November of this year. All who are interested are welcome to contact Barbara Roggema at Barbara.roggema@kcl.ac.uk for more information.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.