Summer School “The Arabic Manuscript: Codicology, Palaeography, and History” Tunis – National Library July 10-15, 2017

The National Library of Tunisia and the University of Strasbourg, with the support of the Barakat Foundation and Max van Berchem Foundation, organize a summer school on “The Arabic Manuscript: Codicology, Palaeography and History,” in Tunis, National Library, July 10-15, 2017.

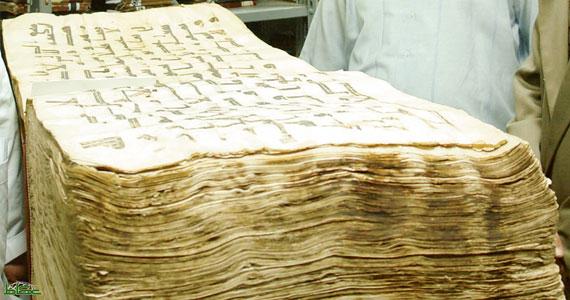

The history of intellectual production, books and libraries in Tunisia is a very rich and long-standing one. The largest collection of premodern, mainly Arabic manuscripts is preserved in the National Library in Tunis. It consists of ca. 25.000 volumes, in addition to thousands of other codices and leaves in the Centre for the Study of Islamic Arts and Civilisation in Raqqada, Kairouan, and in a few other places. This manuscript heritage covers a period of over a millennium (9th – 19th C.) and contains important testimonies to the history of the region.

The summer school aims at offering a substantial training course on the Arabic manuscript with a focus on this heritage. During six days, some of the most eminent specialists in the field will propose theoretical and practical workshop sessions on the different aspects of the subject, especially codicology and palaeography, with the objective of providing the participants with the knowledge and methods necessary to analyse Arabic manuscripts in research, editing or cataloguing projects. Moreover, the participants will have the opportunity to access one of the most important manuscript collections in the Maghreb and the Arab world. They will also be able to visit several other collections, museums and monuments in Tunis and Kairouan.

The speakers include Jean-Louis Estève (Ecole Supérieure Estienne des Arts et Industries Graphiques, Paris) ; Alain George (University of Edinburgh) ; Asma Hilali (Institute of Ismaili Studies, London) ; Mustapha Jaouhari (Université Bordeaux Montaigne) ; Francis Richard (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque Universitaire des Langues et Civilisations, Paris) ; Rachida Smine (National Library of Tunisia) ; Aurélia Stréri (independent book conservator, Paris).

The number of participants is limited. Preregistration is compulsory. Masters’ students, PhD candidates, librarians and researchers working on Arabic manuscripts will be given priority. Please send a short CV and cover letter to manuscritarabetunis@gmail.com before April 30, 2017.

The main languages of the summer school are French and Arabic.

Organisation and contacts: Rachida Smine, Deputy Director of the Manuscript Department, National Library of Tunisia, and/or Nourane Ben Azzouna, Associate Professor, University of Strasbourg: manuscritarabetunis@gmail.com

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2017. All rights reserved.

……………………………..

Ecole d’été : Le manuscrit arabe : codicologie, paléographie et histoire

Tunis – Bibliothèque Nationale de Tunisie, 10-15 juillet 2017

La Bibliothèque Nationale de Tunisie et l’Université de Strasbourg, grâce au soutien de la Barakat Foundation et de la Fondation Max van Berchem, organisent une école d’été intitulée « Le manuscrit arabe : codicologie, paléographie et histoire » à Tunis, à la Bibliothèque Nationale de Tunisie, du 10 au 15 juillet 2017.

L’histoire de la production intellectuelle, des livres et des bibliothèques en Tunisie est particulièrement riche et ancienne. La plus grande collection de manuscrits, essentiellement en arabe, est conservée à Tunis, à la Bibliothèque Nationale. Elle se compose d’environ 25.000 volumes, auxquels s’ajoutent plusieurs milliers d’autres volumes et feuillets au Centre d’Etudes de la Civilisation et des Arts Islamiques à Raqqada, Kairouan, et dans quelques autres collections. Ce patrimoine manuscrit couvre une période de plus d’un millénaire (IXe-XIXe s.) et est riche de témoignages importants de l’histoire de la région.

L’école d’été vise à offrir une formation substantielle sur le manuscrit arabe avec un accent sur ce patrimoine. Pendant six jours, quelques-uns des plus éminents spécialistes des manuscrits arabes proposeront des enseignements théoriques et des ateliers pratiques sur les différents aspects du sujet, en particulier la codicologie et la paléographie, dans le but de permettre aux participants d’acquérir les méthodes nécessaires à l’analyse des manuscrits arabes dans le cadre d’un travail de recherche, d’édition ou de catalogage. De plus, les participants auront l’opportunité d’accéder à l’une des plus importantes collections de manuscrits du Maghreb et du monde arabe. Ils pourront aussi visiter plusieurs autres collections, musées et monuments à Tunis et à Kairouan.

Intervenants : Jean-Louis Estève (Ecole Supérieure Estienne des Arts et Industries Graphiques, Paris) ; Alain George (Université d’Edinburgh) ; Asma Hilali (Institut d’Etudes Ismaéliennes, Londres) ; Mustapha Jaouhari (Université Bordeaux Montaigne) ; Francis Richard (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque Universitaire des Langues et Civilisations, Paris) ; Rachida Smine (Bibliothèque Nationale de Tunisie) ; Aurélia Stréri (restauratrice indépendante, Paris).

Le nombre de places est limité. L’inscription est donc obligatoire. Les étudiants en Master 2 et en Doctorat ainsi que les enseignants, chercheurs, bibliothécaires et professionnels qui travaillent sur les manuscrits arabes sont prioritaires. Envoyez un bref CV et lettre de motivation à manuscritarabetunis@gmail.com avant le 30 avril 2017.

La formation sera essentiellement en français et en arabe.

Les participants qui le souhaitent recevront une attestation de formation.

Organisation et contacts : Rachida Smine, Sous-Directrice du Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque Nationale de Tunisie et/ou Nourane Ben Azzouna, Maître de conférences, Université de Strasbourg : manuscritarabetunis@gmail.com

©Association internationale des études coraniques, 2017. Tous les droits sont réservés.

……………………..

دورة تدريبية: المخطوط العربي: الكوديكولوجيا، الخطوط، التاريخ

المكتبة الوطنية التونسية، 10- 15 جويلية 2017، تونس

تنظم المكتبة الوطنية وجامعة سترازبورغ بمساعدة “مؤسسة بركات” و”مؤسسة ماكس فان برشام” دورة تدريبية بعنوان “المخطوط العربي: الكوديكولوجيا، الخطوط، التاريخ” بالمكتبة الوطنية التونسية، 10- 15 جويلية 2017، تونس.

تزخر تونس بإنتاج فكري غزير ويتبيّن ذلك من عدد مخطوطاتها ومكتباتها. تحتوي المكتبة الوطنية على رصيد ثري من المخطوطات العربية ما يقارب 24.000 مجلد، إلى جانب آلاف المخطوطات بمركز الدراسات الاسلامية برقادة- القيروان وبعض الأرصدة الخاصة. يعكس هذا الرصيد حصيلة ما يزيد عن عشرة قرون من التراكم المعرفي والفني (تقريبا من القرن التاسع إلى القرن التاسع عشر)، ويبرز ما شهدته إفريقية والعالم العربي والإسلامي من إشعاع علمي وثقافي.

وتتناول هذه الدورة برنامجا مكثفا حول المخطوطات العربية عموما والتونسية والمغاربية خصوصا وتشتمل على عدة مداخلات في علم المخطوطات (الكوديكولوجيا) والخطوط والفهرسة وﺍﻠﺘﺤﻘﻴﻖ ويعقب ذلك عدد من ورشات العمل تتناول .التطبيق العملي للمحاضرات النظرية. سيحاضر في هذه الدورة مجموعة من الأساتذة والباحثين المختصين

سيتعرف المشاركون، على هامش هذه الدورة، على المكتبة الوطنية وأرصدتها الثرية، ﺇﻠﻰ ﺟﺎﻨﺐ مركز الدراسات الاسلامية .برقادة، القيروان

:المتدخلون

(المعهد العالي إﻴﺴتيان للفنون والرسوم الصناعية، باريس) Jean-Louis Estève

(جامعة ادنبرة) Alain George

(أسماء هلالي (مركز الدراسات الاسماعيلية، لندن

(مصطفى جوهري (جامعة بوردو، مونتانيو

(المكتبة الوطنية الفرنسية، المكتبة الجامعية للغات والحضارات، باريس) Francis Richard

(رشيدة السمين (المكتبة الوطنية، تونس

(مرمّمة مخطوطات، باريس)Aurélia Stréri

:المشرف على الدورة

(رشيدة السمين (كاهية مدير، المكتبة الوطنية التونسية

(نوران بن عزونة (أستاذة محاضرة، جامعة سترازبورغ

:للاتصال

manuscritarabetunis@gmail.com

:المستفيدون

الطلبة والباحثون المهتمون بالمخطوطات –

اختصاصيو المخطوطات بالمكتبات –

:الزمان والمكان

15-10

جويلية 2017، المكتبة الوطنية، تونس

:المدّة وعددالساعات

أيام 6

يوميا من الساعة 8.00 إلى الساعة 14.30

:لغة الدورة

العربية والفرنسية

:التسجيل

يُرجى إرسال سيرة ذاتية ومطلب مشاركة على الموقع التالي

manuscritarabetunis@gmail.com

الأماكن محدودة لذا يرجى الحجز قبل يوم 30 أفريل 2017

:ملاحظة

تُسلّم في نهاية الدورة شهادة تفيد المشاركة أو الحضور في الدورة التدريبية

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2017. All rights reserved.