مخطوطات القرآن والفيلولوجيا الرقمية: حوار مع الدكتورة البا فيديلي

مخطوطات القرآن والفيلولوجيا الرقمية

حوار مع الدكتورة البا فيديلي

حوار وتحرير: أحمد وسام شاكر

:مدخل

في 22 يوليو 2015، أعلنت جامعة برمنجهام على موقعها الرسمي عن نتائج إجراء الفحص الكربوني المشع لواحدة من المخطوطات القرآنية القديمة التي تحتفظ بها مكتبة الجامعة في قسم الشرق الأوسط،وقد حقق هذا الخبر – الذي بثته البي بي سي أولاً – انتشاراً إعلامياً واسعاً في الصحافة ووسائل التواصل الإجتماعي، وتفاعل معه الكثير من القراء والأكاديميين، وما زال صداه يُسمَع من حين إلى آخر.وعن ردود الأفعال من جانب الجامعة، علقت سوزان واريل مديرة المجموعات الخاصة بأن «الباحثين لم يكن يخطر ببالهم أبداً أن المخطوطة قديمة إلى هذا الحد» ([1]) وأضافت «امتلاك الجامعة صفحات من المصحف قد تكون هي الأقدم في العالم كله أمر في غاية الإثارة»، كما أشار أستاذ المسيحية والإسلام ديفيد توماس إلى أن ناسِخ المخطوطة «ربما عرف النبي محمد، وربما رآه واستمع إلى حديثه، وربما كان مقرباً منه، وهذا ما يستحضره هذا المخطوط»([2]). وكان التحليل الكربوني قد خَلُصَ إلى أن المخطوطة القرآنية تشكلت في الفترة ما بين عامي 568م و645م بنسبة دقة تبلغ 95.4%([3]).ومن نافلة القول الإشارة إلى أن التأريخ بالكربون المشع يقيس عُمْر الوسيط (أي الجلد) لا عُمْر الكتابة ذاتها (أي الحبر)؛ فمن المحتمل نظرياً أن يكون ذبح الحيوان قد تم في الفترة المذكورة لكن الكتابة على جلده جاءت في وقت لاحق. ومع ذلك، فتحليل الكربون المشع المذكور آنفاً يتقاطع مع تحليلات نصية أخرى، ومن ثَمَّ يُمكن اعتبار هذه المخطوطة من جُمْلة المخطوطات القرآنية المنسوخة في القرن الأول الهجري.

– 1 –

تُعرف المخطوطة القرآنية إعلامياً بـ «مصحف برمنجهام» (Birmingham Qur’an) أو برقم: (Islamic Arabic 1572a)، وهي عبارة عن ورقتي رَّقّ تتضمن آياتٍ من سور الكهف ومريم وطه، مكتوبة بالخط الحجازي. لقد ظلت هاتان الورقتان لفترة طويلة مدمجتين خطأً مع مخطوطة قرآنية أخرى، ويعود الفضل للباحثة المشاركة بقسم المنح النصية والتحرير الإلكتروني بالجامعة «البا فيديلي» (Alba Fedeli) التي أدركت أهميتها العلمية ورشحتها لاختبار الكربون المشع. إلى جانب ذلك، تمكنت فيديلي من اقتفاء آثار (16) ورقة أخرى محفوظة اليوم في المكتبة الوطنية الفرنسية اتضح أنها تتطابق كوديكولوجياً مع ورقتي برمنجهام؛ أي أن الإثنين يشكلان مصحفاً واحداً تناثرت أوراقه عبر الزمن. يعود هذا المصحف الذي تفرَّقَت أوراقه بين باريس وبرمنجهام، وأماكن أخرى لا تزال مجهولة، إلى جامع عمرو بن العاص في الفسطاط بمصر القديمة.

– 2 –

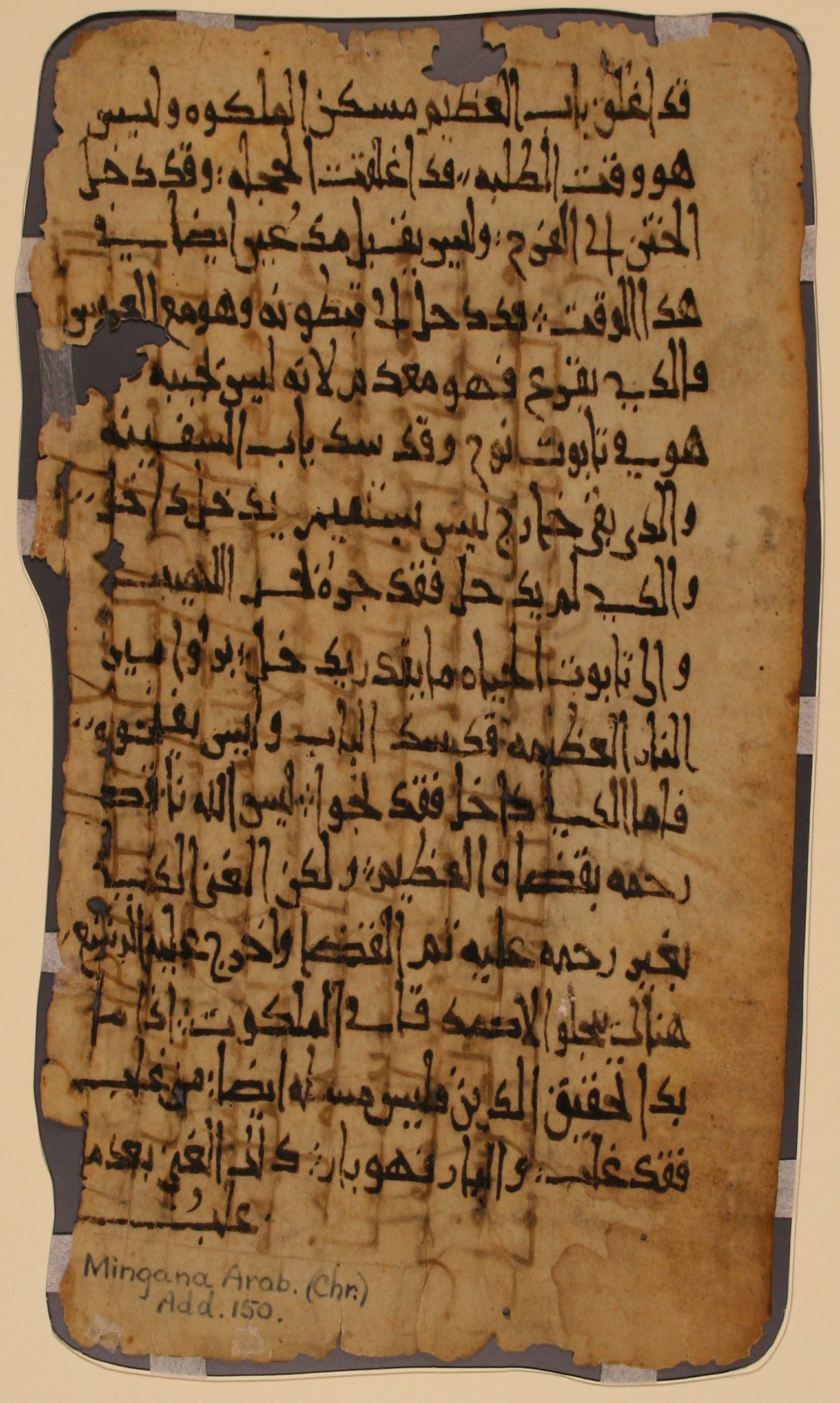

تخرجت البا فيديلي من الجامعة الكاثوليكية بميلانو عام 2000 على يد المستعرب سرجو نويا نوزاده (2008-1931)، ثم ما لبِثَت أن دَرَّست لفترة في الجامعة الحكومية، قبل أن تنتقل إلى جامعة برمنجهام عام 2011. في برمنجهام، اشتغلت فيديلي على دراسة المخطوطات القرآنية المحفوظة في مكتبة كادبوري للبحوث ضمن مجموعة المستشرق الكلداني ألفونس منجانا (1878-1937). ويُذكر أن مجموعة منجانا تحتوي على أكثر من 3000 آلاف مخطوطة شرقية مكتوبة بأكثر من 20 لغة؛ من بينها مقتطفات قرآنية مبكرة، بعضها نادر جداً كالبردية (IX.16) التي تعود للقرن الثاني الهجري. وبعد أربع سنوات من العمل، حصلت فيديلي صيف عام 2015 على درجة الدكتوراه من قسم اللاهوت والدين بالجامعة عن أطروحتها: «المخطوطات القرآنية، ونصّها، وأوراق ألفونس منجانا في قسم المجموعات الخاصّة التابع لجامعة برمنجهام»)[4](؛ والتي لقيت على إثرها ترحيباً في موطنها الأم إيطاليا حيث اختارتها صحيفة (كوريري ديلا سيرا) كواحدة من بين 43 امرأة محبوبة على مستوى العالم لسنة 2015م([5]).

وفي الوقت الراهن، تستأنف فيديلي بحوثها لمرحلة ما بعد الدكتوراه في مركز الدراسات الدينية بجامعة أوربا الوسطى حيث بدأت مشروعاً جديداً يُركِّز على دراسة المخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة وفهم العلاقة المشتركة بين نصوصها عبر استخدام برمجيات شجرة التطور (Phylogenetic software) ([6]).

– 3 –

إن لدراسة المخطوطات القرآنية القديمة تاريخاً طويلاً في الأكاديمية الغربية يمتد لأكثر من مئتي عام، حيث ظهر هذا الاهتمام البحثي – كما يذكر فرانسوا ديروش – في آواخر القرن الثامن عشر على يد المستشرق واللاهوتي الدنماركي جاكب جورج كريستيان أدلر (1834-1756) الذي كان مهتماً بالكتابات الكوفية ودَرَسَ عدداً من المخطوطات القرآنية المحفوظة في المكتبة الملكية بكوبنهاجن([7]). وإذا تتبعنا إصدارات المخطوطات القرآنية خلال تلك الحقبة؛ لوجدنا أنها لا تخرج عن صنفين: الدبلوماتيك والفاكسميليا. كذلك، وجِدَت مبادرة في النصف الأول من القرن العشرين لإخراج نسخة نقدية لنص القرآن اعتماداً على أفضل وأقدم المخطوطات المتوفرة لكنها باءت بالفشل بسبب الحرب العالمية وتبعاتها، وغيرها من الأسباب التي يطول شرحها في هذا المقام.

أما في القرن الواحد والعشرين، فقد اختارت فيديلي مقاربة جديدة؛ غير مسبوقة، ترتكز على استثمار أدوات العلوم الإنسانية الرقمية لتحليل نصوص المخطوطات القرآنية، والتعليق عليها، ونشرها إلكترونياً على الويب.

في الحوار – التالي – الذي أجريناه مع الدكتورة فيديلي، حاولنا تسليط الضوء على عدة جوانب، منها: حياتها العلمية؛ طبيعة بحوثها ومشاريعها وكيف أسهمت «الفيلولوجيا الرقمية» في صياغة رؤيتها المستقبلية لدراسات المخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة؛ وغير ذلك من القضايا التقنية التي تهم دارسي المخطوطات القرآنية. ولأجل المصطلحات الكوديكولوجية الواردة في الحوار، وضعنا ملحقاً خاصاً بها في آخر اللقاء لكي يتسنى للقارئ الرجوع إليها.

في الختام، يُنصَح القارئ الذي يريد مزيد توسع، بقراءة دراسات البا فيديلي المبثوثة في أعداد المجلة الدولية للمخطوطات الشرقية «Manuscripta Orientalia»؛ وكذلك أطروحتها للدكتوراه عن مجموعة منجانا التي ستتاح إلكترونياً في مايو 2017.

نص الحوار:

أحمد شاكر (شاكر): كيف بدأ اهتمامك بالمخطوطات القرآنية؟

البا فيديلي (فيديلي): لطالما كنت مأسورة بالمخطوطات على اختلاف تقاليدها الكتابية. عندما كنت طفلة صغيرة، كانت المخطوطات هي تلك الأشياء المدهشة التي تحوي في طياتها قصصاً مثيرة جداً، وبعد ذلك رأيت أنها كأشياء مادية مكنتني أيضاً من الوصول المباشر إلى أعمال وحكايات مشوقة عبر تفحص طبقاتها المختلفة. وبعد إنهائي دراسة الكلاسيكيات، واصلتُ – مفتونة باللغات والخطوط –دراسة اللغتين اللاتينية واليونانية ولغات أخرى كالعربية. عبر طريقي، قابلت سرجو نويا نوزاده (1931-2008) الذي أوحى إلي دراسة المخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة. كان الأمر مزيجاً بين العاطفة الشخصية وحُسن الحظ في لقاء معلم جيد.

شاكر: باعتبارك زميلة باحثة في معهد المنح النصية والتحرير الإلكتروني التابع لجامعة برمنجهام، هل يمكنك أن تحديثنا أكثر عن مشروعك حول النسخة الإلكترونية للمخطوطات القرآنية في مجموعة منجانا؟

فيديلي: حين اكتشفت شطراً من ورقة برمنجهام (Mingana Chr. Arab. Add. 150) والتي كانت تنتمي فيما مضى إلى «طِرس كامبريدج القرآني-Or. 1287» (ويُعرف أيضاً بطِرس منجانا-لويس)، قمت بالتواصل مع ديفيد باركر وأعضاء فريق معهد المنح النصية والتحرير الإلكتروني بجامعة برمنجهام؛ وهم رواد في دراسات المخطوطات والفيلولوجيا الرقمية. لقد قدموا للعلماء منهجاً حديثاً لدراسة وتحرير المخطوطات مما ألهمنا أفكاراً بحثية جديدة. كنت أرغب بدراسة منهج الفيلولوجيا الرقمية فإذا بعَالَمٍ جديد يفتح لي أبوابه. من هنا، قدمت مقترحاً لدراسة المخطوطات القرآنية في مجموعة منجانا وتطبيق منهج الفيلولوجيا الرقمية عليها. رحب معهد المنح النصية والتحرير الإلكتروني بالمقترح ووفر لي الدعم البحثي اللازم، وقد أشعرني ذلك بأنني أعتمدت أكاديمياً بالفعل بعد وفاة نويا نوزاده. قمت خلال مشروع برمنجهام (2011-2015) بدراسة المخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة في مجموعة منجانا، ومن بينها ما أسميه «مصحف البي بي سي» (BBC Qur’an)، حيث دَرَّبت نفسي جيداً على ترميز نصوص المخطوطات بواسطة الفيلولولجيا الرقمية.

تتوفر حصيلة جزئية من نتائج أعمالي في مستودع موقع جامعة برمنجهام و مكتبة جامعة كامبريدج الرقمية. بإمكاني أن أشرح لك، وأزعجك، بكافة تفاصيل نظام الترميز الذي قمت ببناءه كي أتمكن من استيعاب نصوص المخطوطات، وعرضها، وجعلها قابلة للبحث، لكن الطريقة الأسهل هي أن أدعوك لتصفح النسخة الإلكترونية من طِرس منجانا-لويس أو تتبع تحركات صورة الطِرس أثناء عملية إعادة بناءه.

شاكر: ما أهمية الفيلولوجيا الرقمية وكيف أثَّرَت على بحوثك؟

فيديلي: تُعَد الفيلولوجيا والأدوات/المناهج الرقمية ثورةً في مجال العلوم الإنسانية، وقد أحدثت ثورة في بحوثي كذلك؛ مغيرة نظرتي كلياً نحو المخطوطات القرآنية. لقد أسهم الإجتماع المنعقد في معهد المنح النصية والتحرير الإلكتروني واقتراح استخدام منهج الفيلولوجيا الرقمية، أسهم بتشكيل رؤيتي المستقبلية بخصوص تحرير المخطوطات القرآنية بهدف إنتاج أرشيف ثري يعرض جميع الشواهد المخطوطية، ويفسر عملية إنتاج نصوص المخطوطات والسياق الذي كُتِبَت فيه. كان هذا المنهج مختلفاً عن الأمثلة السابقة لإصدارات المخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة، ومختلفاً كذلك عن عملي السابق مع البروفيسور الراحل نويا نوزاده. إن الثراء الكلي لتقاليد المخطوطات يستبدل الفكرة التقليدية لإخراج نسخة نقدية للنص القرآني (أي بالمعنى الأوربي لاسترجاع النسخة الأم)، حيث يقوم التحرير الرقمي ببناء قاعدة بيانات معلوماتية حول نصوص المخطوطات وفق نظام لاخطي مماثل للبعد الإلكتروني؛ لا يعتمد على أسطر النص المطبوع؛ لكي ينتج نصاً قابلاً للبحث من الداخل ومنجماً من المعلومات، وفقاً لنظام الترميز والمرمِز. هذا هو سبب قيامي بترميز نص طِرس منجانا-لويس وإدخال ملاحظات تحريرية، مُلحَقَةً – على سبيل المثال– بوسم «مورفولوجيا». هذا يعني أن الكلمات المنسوخة في الإصدار الرقمي يرافقها نافذة منبثقة تُظهِر للمستخدم أن سبب اختلاف الكلمة هاهنا مرتبط – على سبيل المثال – بغياب علامات الإعراب (بقدر ما نعرفه من قواعد اللغة العربية المبكرة). يستطيع المستخدم أن يقرأ عن ظاهرة «غياب الحالات» في حين أن فئة «مورفولوجيا» غير مرئية بالنسبة له، لكنها تبني قاعدة بيانات معلوماتية من الداخل؛ في هذه الحالة من الناحية اللغوية.

أدرب نفسي حالياً على ترميز نصوص المخطوطات بهدف إنتاج قاعدة بيانات مستخلصة من النَسْخ النصي، بشكل يتوافق مع برمجيات شجرة التطور؛ وهو عمل في طور التنفيذ ضمن بحوثي الجارية لمرحلة ما بعد الدكتوراه في مركز الدراسات الدينية بجامعة أوربا الوسطى في بودابست. إنني أسعى لتحويل الثراء الكلي للمخطوطات إلى سلسلة من الحروف أو الرموز كما هو الحال بالنسبة لتحليل تسلسل الحمض النووي (DNA). يكمن النهج المبتكر لدراسة المخطوطات القرآنية في استخدام برامج الحاسوب التي تم تطويرها لصالح علم الأحياء التطوري، فقد تم اكتشاف أن تاريخ العلاقات بين المخطوطات مماثل للتاريخ التطوري للكائنات الحية. يجب أن تكون هناك صلات مشتركة بين المخطوطات، ولا ينبغي أن تُقدَّم كعناصر منفصلة، كما رأينا في حالة «مصحف برمنجهام» أو «مصحف البي بي سي».

شاكر: في الأشهر الماضية، تناقلت الصحف مئات المقالات عن «مصحف برمنجهام» الذي أعاده الفحص الكربوني المشع إلى الفترة 568-645م بنسبة دقة تصل إلى 95.4% وقد ارتبط هذا الكشف باسمك. ما تقييمك العام لردود الأفعال على الخبر من فئات كبيرة كالمؤمنين، غير المتخصصين، والأكاديميين، على حد سواء؟

فيديلي: لقد حاولت فهم هذه الظاهرة من منظور تاريخي عبر مقارنتها بحالات سابقة مماثلة، وإن اختلفت طرق ترويجها ومستوى الانتشار الذي حققته في الإعلام (أي الصحف المطبوعة والإتصالات الإلكترونية ما قبل الويب 2.0). لقد كان للبعد الإعلامي للصحيفة المطبوعة دوراً بارزاً في استقبال خبر إصدار منجانا ولويس لطِرس كامبريدج وعنوانه الفرعي المثير للجدل عن قائمة الاختلافات التي يُرجَح أنها تسبق الجمع العثماني: «أوراق من ثلاثة مصاحف قديمة» (1914). في حين أثَّرَت بيئة ما قبل الويب 2.0 في استقبال خبر طِرس صنعاء المشار إليه في مقالة توبي لستر: «ما القرآن؟» (1999). أما في بيئة الويب 2.0، فالمثال الأقرب للمقارنة هو الإعلان عن المخطوطة القرآنية في جامعة توبنغن في نوفمبر عام 2014. في المثال الأخير، تردد صدى ذلك الخبر على مستوى الويب بأكلمه. مع ذلك، فهذا الانتشار الواسع لا يُقارن بخبر الإعلان عن «مصحف برمنجهام» الذي بلغ عدد قراءه الـ 450 مليون قارئ.

يشير تحليلي لردود الأفعال – والذي يشمل بطبيعة الحال موقفي من القصة برمتها – إلى الدور الفاعل الذي يؤديه الإعلام ووسائل التواصل الإجتماعي. لقد منحني تحليلي الشخصي لأصداء خبر «مصحف برمنجهام» أفضلية في تحديد مواطن الالتباس والتضليل في سلسلة الأخبار الصحفية. ما زلت أحلل ما حدث والأسباب وراء تفجر الفضول حول نتائج تحليل الكربون المشع. الواقع أن استخدام موقع البي بي سي لاسم التفضيل «أقدم» في العنوان الرئيسي للمقال، لعب دوراً مهماً في إثارة الانتباه من مختلف أنحاء العالم، ومن كافة الأصعدة؛ نحو مخطوطة شبيهة بمخطوطات قرآنية معروفة؛ بعضها منشور مسبقاً.

شاكر: في عام 1998 و2001، نشر فرانسوا ديروش والبروفيسور الراحل سرجو نويا نوزاده نسخاً طبق الأصل لمصحفين قديمين، الأول محفوظ في باريس (Arabe 328a، 56 ورقة) والثاني في لندن (Or.2165، 61 ورقة). ماذا كان دورك في هذا المشروع؟ وهل تعملين حالياً على نشر مقتطفات قرآنية معينة كنسخة طبق الأصل؟

فيديلي: حين بدأت العمل مع نويا نوزاده كان مجلد مخطوطة باريس قد شارف على الانتهاء ويُجَهَّز للطبع، وقد حضرت آنذاك حفل تدشين الكتاب في المكتبة الوطنية الفرنسية بباريس. بعدها، ساعدت نويا في مراجعة النسخ النصي لمخطوطة لندن (وبعد ذلك فقط أدركت أنه اختار هذه الطريقة ليطلعني بها على دراسات المخطوطات القرآنية ويعلمني شيئاً من خلال التجربة المباشرة). لاحقاً، عملت على إعداد نُسَخ فاكسميلية لمخطوطات قرآنية لم يسبق نشرها من قبل، وهي عبارة عن مقتطفات متناثرة في عدة مؤسسات حول العالم كفينا، وبرلين، والفاتيكان، ولندن، والقاهرة. كما قمت، جزئياً، بنسخ نصوص أوراق المجلد الثاني من مخطوطة لندن. وفي الفترة الأخيرة التي سبقت وفاة نويا، كنت أعمل على طِرس صنعاء ونَسْخ نصه؛ وقد قامت مكتبة كامبريدج الرقمية مؤخراً برفع أعمالي حول طِرس منجانا-لويس.

أركز حالياً على دراسة أجزاء محددة من النص القرآني في مخطوطات متنوعة لفهم تاريخ الانتقال الكتابي للنص بواسطة برمجيات شجرة التطور. لقد صار بإمكاني اليوم رؤية أول شجرة تطورية من صُنعي. تأبى الفيلولوجيا الرقمية إلا أن تسير بي نحو رقمنة المخطوطات وعرضها على الويب، لكني ما زلت أرغب باستكمال العمل الذي بدأته مع مُعلِّمي الراحل نويا نوزاده في النشر التقليدي لنصوص المخطوطات وصورها الفاكسميلية. قد تكون مخطوطة مكتبة جامعة توبنغن (Ma VI 165) هي أولى أعمالي القادمة في هذا السياق، لكن من يدري فربما أعثر على مخطوطة أكثر أهمية من توبنغن وأنشرها، رغم أن العلوم الإنسانية الرقمية تناديني بإتجاهٍ آخر تماماً.

شاكر: لقد زرتي أيضاً دار المخطوطات في اليمن وأتيحت لكِ فرصة الإطلاع على المخطوطات القرآنية المحفوظة في الجامع الكبير بصنعاء، وهو المكان الذي عُثِرَ فيه على آلاف الرقوق القرآنية في سبعينيات القرن الماضي. ما هي أخر تحديثات الرحلة اليمنية لدراسة ورقمنة هذه المخطوطات؟

فيديلي: إنك على الأغلب تشير إلى البعثة التي انطلقت في أكتوبر عام 2007 والتي قمنا خلالها برقمنة طِرس صنعاء ومخطوطتين أُخرتين. لسوء الحظ، توفي نويا نوزاده في حادث سيارة بعد بضعة أشهر فقط وانتقل المشروع والصور إلى الفريق الفرنسي ومن ثم إلى فريق برلين. يستكمل علماء الفريق الألماني-الفرنسي العمل على هذا المشروع – لبضع سنوات الآن – منذ وفاة نويا عام 2008.

أما إذا كنت تقصد المخطوطات الجديدة التي اكتشفت في الجامع الكبير عام 2007، فقد شاركت في أول دراسة مسحية لها عام 2008. لاحقاً، حالت الأوضاع السياسية في اليمن دون تمكين الفريق الإيطالي من استكمال العمل على المشروع، لكني ما زلت آمل أن تتاح لي الفرصة لدراسة وفهرسة هذه المخطوطات المدهشة. التحلي بالصبر أمرٌ ضروري عند التعامل مع المخطوطات.

شاكر: كُتِبَت كلمة «طوى» (طه: 12) في عدد من المخطوطات القرآنية على شكل «طاوى» وهو مايتفق مع بعض القراءات الشاذة كما ذكرتِ أنتِ في أكثر من مناسبة. لكن أليس من الممكن أيضاً أن تكون هذه ظاهرة كتابية تتعلق بزيادة الألف؛ أي أن الألف تكتب فعلاً لكنها لا تنطق في واقع الأمر؟

فيديلي: حتى لو فسرتَ «طاوى» باعتبارها قراءة مخالفة لقواعد الهجاء فهي لا تزال منقولة ضمن القراءات الشاذة. على أي حال، فإن هجاء كلمة «طوى» لا يوافق هيكل «طاوى». حقيقة أن «طاوى» مكتوبة بهذا الشكل في بعض المخطوطات هو أكثر أهمية من نوع ومعنى القراءة. إن قيمة ذلك يكمن في احتمالية وجود صلة مشتركة بين المخطوطات التي تثبت نفس القراءة. قراءة «طاوى» وغيرها من القراءات المتكررة في المخطوطات – بمعزل عن كونها متواترة أو شاذة – هي التي دفعتني لإعداد مشروعي عن التحليل التطوري للمخطوطات القرآنية.

شاكر: هذا ينقلنا إلى مسألة أخرى حول العلاقة بين الشفوي والكتابي في نقل النص. هل كان النساخ الأوائل يستعينون بذاكرتهم – على الأقل جزئياً – في كتابة نص القرآن على الرقوق أم أنهم كانوا ينقلون بشكل أساسي من أصول خطية؟

فيديلي: لا أملك إجابة مطلقة على سؤال هل كان النسَّاخ، ككيان متجانس فريد في نوعه وسلوكه، يملون النص من حفظهم أو من نُسَخ خطية مكتوبة. هناك مخطوطات تشير بوضوح إلى أن النُسَّاخ كانوا يعتمدون في نسخها على أصول خطية، وهناك حالات أخرى يمكنك فيها افتراض أن النُسَّاخ كانوا يملون من حفظهم. في الواقع، فإن نوعية الأخطاء النسخية التي يرتكبها النُسَّاخ تعكس إما عملية نقل بصرية من أصل مخطوط أو عملية ذهنية لناسخ يحاول استذكار النص. بالتالي، ليست لدي إجابة عامة ولكن مجموعة ملاحظات محددة من المخطوطات التي تمكَّنت من الإطلاع عليها ودراستها حتى الآن. ومن الأمثلة على ذلك «مصحف البي بي سي»، حيث تشير نوعية الأخطاء النسخية فيه إلى أنه منسوخ من أصل مخطوط.

يجب أن تُدرَس كل مخطوطة وفقاً لحالتها الخاصة؛ أنا أقارب النص من خلال انتقاله الكتابي وليس من خلال روايات التقليد الإسلامي، فبإمكاننا تفسير الثقافة الدينية وفقاً لما تنتجه من نصوص مقدسة بدلاً من تفسير النصوص المقدسة وفق الثقافة.

شاكر: نرصد في المصاحف المبكرة ظاهرة القراءات «المزدوجة» أي ظهور قراءات متواترة وشاذة في المخطوطة الواحدة. ما تعقيبك على هذه القضية؟

فيديلي: هذا هو المشروع الذي بدأته مؤخراً في جامعة أوربا الوسطى ببودابست (المجر) حيث أقوم، بمساعدة أحد فنيي تكنولوجيا المعلومات، بتجميع وتحليل عدد من المخطوطات القرآنية لكي يتسنى لنا معرفة العلاقة المشتركة بينها من خلال استخدام برمجيات شجرة التطور. وبعد إكمال تحليل المخطوطات المُجَمّعَة اعتماداً على الأدلة النصية الداخلية فقط، سأقوم بمقارنة نصوص المخطوطات مع ما تذكره كتب القراءات. بحسب ما أمكنني الإطلاع عليه حتى الآن، فنصوص المخطوطات المُجَمّعَة لا تتفق كلياً مع تقاليد القراءات، إذ تتقاطع الأدلة المباشرة (المخطوطات) مع الأدلة غير المباشرة (القراءات) في بعض المواضع فقط.

شاكر: نستخدم عادة مصطلح «حجازي» أو «مائل» لوصف الشكل المبكر للكتابة العربية، فما هي أصول هذا المصطلح؟ وما هي أبرز خصائصه؟

فيديلي: «حجازي» هو مصطلح صاغه العالِم الإيطالي ميكيلي أماري (1806-1889)؛ وعلى أساسهكرَّس نويا نوزاده وديروش مشروعهما لنشر النُسَخ الفاكسميلية للمخطوطات القرآنية (مشروع أماري). قام أماري بدراسة وفهرسة المخطوطات القرآنية المبكرة في المكتبة الوطنية الفرنسية وعين خطوطها استناداً إلى وصف النديم في كتاب الفهرست للخطوط العربية المبكرة من مكة والمدينة. تكمن السمة الأساسية لهذه الخطوط في مظهرها العام الذي يتميز بشكل رأسي مستطيل مائل نحو اليمين، وبصفة خاصة، الشكل المميز للألف المائلة عند قاعدتها. وهكذا، يشير مصطلح حجازي (أي الخط المكي أو المدني) إلى المكان المحتمل الذي نشأ فيه الخط مع أننا نجهل الأصل الجغرافي لجميع المقتطفات القرآنية التي نطلق عليها تسمية المخطوطات الحجازية. مع ذلك، فهو تعريف سهل وفعّال للإشارة إلى هذه المقتطفات.

أما مصطلح «مائل» فهو من صياغة العالِم النمساوي جوزيف فون كاراباشيك (1845-1918) ويشير إلى المظهر العام للخط، مع الأخذ بنظر الاعتبار عدم وجود اتفاق بين العلماء حول تعريف واستعمالات هذا المصطلح.

شاكر: هناك خلاف بين العلماء حول تأريخ المصاحف التي لا تحتوي على قيد الختام. ما هو تقييمك لهذا الخلاف؟ وما هو موقفك؟

فيديلي: لا ينبغي فصل نتائج التأريخ بالكربون المشع عن التسلسل الزمني النسبي (الكرونولوجي) الذي ينشأ من خلال تحليلات أخرى كالباليوغرافيا، التحليلات النصية واللغوية، والمقارنات مع الشواهد المعاصرة المتاحة. لقد كُتِبَت كل مخطوطة – علينا أن نضع في الاعتبار دائماً أن المخطوطات المبكرة ليست سوى مقتطفات لا أكثر – في لحظة دقيقة وفريدة من التاريخ ومن ثَمَّ ينبغي أن تتلاقى جميع الطرق الممكنة معاً لإعطاء تسلسل زمني مطلق أو نسبي للمخطوطة. يتوجب على العلماء عدم الاكتفاء بمنهجية واحدة للتأريخ (مثل نتائج الكربون المشع) من دون معرفة المظاهر الأخرى للمقتطفات. فضلاً عن ذلك، وبالنظر إلى أن هذه المخطوطات ليست سوى مقتطفات، فينبغي دراستها معاً كمكون واحد بجانب المكونات الموازية من القطع الأثرية المعاصرة.

أما عن موقفي، فأنا حذرة في عدم استخدام نتيجة تحليل الكربون المشع لوحده دون غيره من التحليلات ودون فحص المخطوطة ذاتها من الناحية النصية والكوديكولوجية.

ملحق: توضيح المصطلحات الكوديكولجية الواردة في الحوار([8]):

– طِرس (Palimpsest): رقّ أخفِي نصّه الأصلي بالحكّ أو بالغسل أو بغير ذلك لنسخ نصّ جديد.

– طبق الأصل / فاكسميليا (Facsimile): نسخة مطابقة للأصل وتامّة لوثيقة أو مخطوطة، مصوّرة ومطبوعة بالقياس الحقيقي.

– نسخة نقدية (Critical edition): طبعة نصّ مبني على المقابلة بين مختلف حالات ذلك النصّ في مخطوطات مختلفة ينتج عنه إبراز تلك الفروق.

– النسخة الأم (Archetype): نسخة معروفة أو مفترضة قد تكون الأصل لكلّ النسخ الباقية من نصّ ما.

– مقتطف (Fragment): مقطع من نصّ ما اقتُطع عمدًا من مجموعة أوسع.

– قيد الختام (Colophon): عبارة ختاميّة يُشار بها الى تأريخ ومكان النسخ وإلى اسم الناسخ.

([1]) شون كوغلان، العثور على صفحات من إحدى “أقدم” نسخ المصحف في جامعة برمنغهام، بي بي سي، 22 يوليو 2015.

([2]) السابق.،

([3]) “Birmingham Qur’an Manuscript Dated Among the Oldest in The World”. 2016.University of Birmingham.

http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/2015/07/quran-manuscript-22-07-15.aspx.

([4]) “Early Qur’ānic Manuscripts, Their Text, And The Alphonse Mingana Papers Held In The Department Of Special Collections Of The University Of Birmingham “. 2016. Etheses Repository. http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/5864/.

([5]) “Le Donne Che Ci Sono Piaciute Nel 2015”. 2016. Corriere Della Sera. http://27esimaora.corriere.it/articolo/le-donne-che-ci-sono-piaciute-nel-2015/.

([6]) “Alba Fedeli Awarded CEU Postdoctoral Religious Studies Research Fellowship”. 2016. Central European University. http://www.ceu.edu/article/2015-09-22/alba-fedeli-awarded-ceu-postdoctoral-religious-studies-research-fellowship.

([7]) Déroche, François. 2014. Qur’ans Of The Umayyads. Leiden: Brill. P. 1.

([8]) التعريفات المذكورة مُستقاة من «المعجم الكوديكولوجي» على الإنترنت http://codicologia.irht.cnrs.fr)).

Originally published on the website of the Namaa Center for Research and Studies, republished with the kind permission of Ahmed Shaker.