Two Unique Translations of the Qurʾan

By Gabriel Reynolds

If you can’t judge a book by its cover perhaps you can by its title. The “Hilali-Khan” translation of the Qurʾan is entitled Interpretation of the Meanings of the Noble Qurʾan in the English Language: A Summarized Version of At-Ṭabarī, Al-Qurtubi and Ibn Kathir with comments from Sahih al-Bukhari. With this title readers are reminded that a translation of the Qurʾan should not be confused with the Qurʾan itself, even while they are assured that this translation is based on reliable Sunni authorities who interpret the Qurʾan in the light of hadith. The Hilali Khan translation is published by Dar-us-Salam, a Saudi publisher (with an American office in Houston) connected with the King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Qurʾan in Medina. In fact the translation of Muhammad Taqi al-Din al-Hilali (of Saudi Arabia) and Muhammad Muhsin Khan (of Pakistan, translator of the Dar-us-Salam Arabic-English version of Bukhari’s Sahih) is subsidized by the Saudi government and distributed for free in many mosques and to many libraries throughout the English speaking world; it was chosen to replace the translation of Yusuf Ali, a translation considered suspect by certain tradition-minded Sunnis.

However, the Hilali-Khan translation has been criticized for the manner in which hadith – including those with an anti-Jewish or anti-Christian flavor — are integrated into the translation. The most famous example of this is verse 7 of al-Fatiha, which Hilali-Khan renders: “The Way of those on whom You have bestowed Your Grace, not (the way) of those who earned Your Anger (such as the Jews), nor of those who went astray (such as the Christians).” Yet it seems to me that there is something felicitous about the interpretive style of Hilalli-Khan translation. All translations in the end are interpretations, and at least Hilali-Khan are truthful in their advertising. In addition, their translation offers frequent citations (in English) of those hadith which are central to the tradition-minded Sunni reading of the Qurʾan. For example, on Q 17:79 (which refers to a maqam mahmud, “a station of praise”) they cite the following hadith, “On the Day of Resurrection the people will fall on their knees and every nation will follow their Prophet and they will say, “O so-and-so! Intercede (for us with Allah)’, till (the right of) intercession will be given to the Prophet (Muhammad) and that will be the day when Allah will raise him to Maqam Mahmud.” These sorts of references make Hilali-Khan a useful reference work.

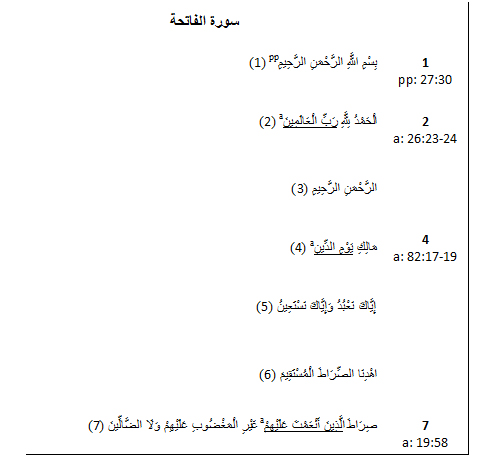

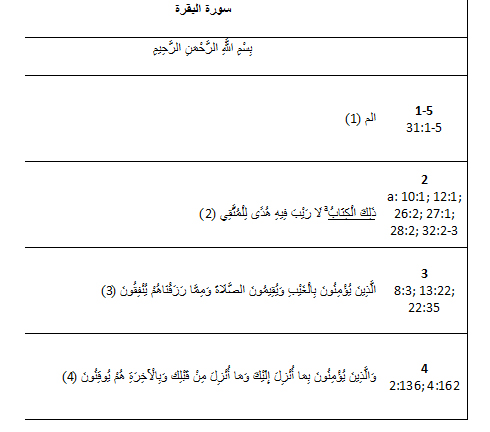

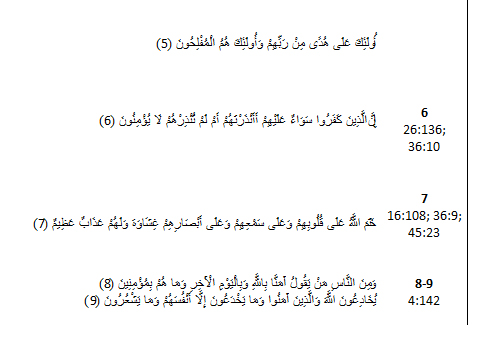

Quite unlike the English translation of Hilali-Khan, and yet unique and useful in its own way, is the French translation of (the Swiss-Palestinian) Sami Awad Aldeed Abu-Sahlieh. One thing that Abu-Sahlieh’s translation does have in common with that of Hilali-Khan is a long title: Le Coran: Version bilingue arabe-française, ordre chronologique selon l’Azhaar, renvois aux variantes, abrogations et aux écrits juifs et chrétiens (The Qurʾan: A Bilingual Arabic French Version in the Chronological Order of al-Azhar, with References to Variants, Abrogations, and Jewish and Christian Writings). As advertised, the translation of Abu-Sahlieh begins not with al-Fatiha but instead with al-ʿAlaq (96) the Sura which appears first in most traditional lists of the chronological order in which the angel Gabriel revealed the Qurʾan to the Prophet. It ends not with al-Nas (114) but with al-Nasr (110).

Meanwhile Abu-Sahlieh includes references throughout his translation to traditional variant readings (qiraʾat), to reports on which verses (according to the tradition) abrogate or are abrogated, and to parallel or otherwise relevant texts from the Bible or other Jewish and Christian writings, notably the Talmud. Thus for the ending of Qurʾan 9:77 yakdhibuna (“They used to tell lies”) Abu Sahlieh notes the variant yukadhdhibuna (“They used to deny”). Three verses later, regarding Qurʾan 9:80 (“Whether or not you ask forgiveness of them, even if you ask forgiveness of them seventy times, God will never forgive them….”) Abu Sahlieh notes: A. the verse is abrogated by Q 63:5 and B. 70 is the same number given for mutual forgiveness in Matthew 18:22. Readers might be critical of certain aspects of Abu Sahlieh’s approach, but they will likely also be grateful for the references that make his translation, like that of Hilali Khan, a useful reference work.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2012. All rights reserved.