Understanding dīn and islām in Q 5:3

by Rachid Benzine*

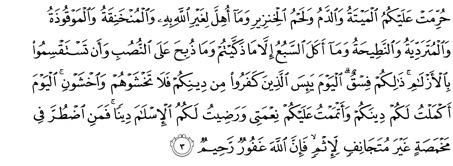

It seems that the section of Q 5:3 that reads “al-yawm akmaltu la-kum dīnakum…al-islām dīnan” is an interpolation inserted between two parts of the verse that should be read continuously, as they pertain to dietary restrictions and to exemptions in life-threatening situations or in case of force majeure (cf. Q 2:175 and 16:115). The key words in the interpolated section are dīn and islām, with islām possibly meaning “being in the act of islām,” referring to various modalities of joining a protection contract with God.

In order to better understand this section of Q 5:3, it is helpful to compare various translations:

Yusuf Ali: “This day have those who reject faith given up all hope of your religion: yet fear them not but fear Me. This day have I perfected your religion for you, completed My favour upon you, and have chosen for you Islam as your religion.”

Pickthal: “This day are those who disbelieve in despair of (ever harming) your religion; so fear them not, fear Me! This day have I perfected your religion for you and completed My favour unto you, and have chosen for you as religion al-Islam.”

Jacques Berque: “Aujourd’hui les dénégateurs désespèrent (de venir à bout) de votre religion. Ne les craignez pas; craignez-moi. Aujourd’hui j’ai parachevé pour vous votre religion, parfait pour vous mon bienfait en agréant pour vous l’islam comme religion.”

Hamza Boubakeur: “Aujourd’hui les mécréants désespèrent (de vous détourner) de votre religion. Ne les redoutez pas; redoutez moi. Aujourd’hui j’ai parachevé pour vous votre religion, vous ai comblé de mon bienfait et ai agréé l’islam comme doctrine religieuse pour vous.”

It is also instructive to compare the use of islām and dīn in other Qur’anic verses. The word islām appears in Q 61:7: “Who does greater wrong than the one who forges a lie against Allah, even if he is being invited to islām? And Allah does not guide those who do wrong” (trans. Yusuf Ali). The meaning of the verbal noun islām is complicated, and best understood in light of its foundational meaning as a verb (aslama), as in Q 2:112: “man aslama wajhahu lillāh.” This phrase should not be translated as “whosoever surrendereth his purpose to Allah” (Pickthall) or “whoever submits his whole self to Allah” (Yusuf Ali), but more accurately as “he who turns his face towards God” in an act of salām. This would mean that the person approaches God peaceably, without any hostility, which enables him to receive God’s protection and guidance (as Q 61:7 indicates with the word hudā). Thus islām is actually a contractual relationship between man and God.

It is also instructive to compare the use of islām and dīn in other Qur’anic verses. The word islām appears in Q 61:7: “Who does greater wrong than the one who forges a lie against Allah, even if he is being invited to islām? And Allah does not guide those who do wrong” (trans. Yusuf Ali). The meaning of the verbal noun islām is complicated, and best understood in light of its foundational meaning as a verb (aslama), as in Q 2:112: “man aslama wajhahu lillāh.” This phrase should not be translated as “whosoever surrendereth his purpose to Allah” (Pickthall) or “whoever submits his whole self to Allah” (Yusuf Ali), but more accurately as “he who turns his face towards God” in an act of salām. This would mean that the person approaches God peaceably, without any hostility, which enables him to receive God’s protection and guidance (as Q 61:7 indicates with the word hudā). Thus islām is actually a contractual relationship between man and God.

As for the word dīn, it cannot be adequately translated as “religion.” It rather expresses the idea of a way or path, as in Q 109:6: “lakum dīnukum wa-lī dīn (to you your way [conduite] and to me mine),” and in Q 30:43: “aqim wajhaka lil-dīn al-qayyim min qabl an ya’tiya yawm lā maradd lahu min Allāh (follow [turn your face towards] the right path before there comes the day when there is no chance to escape from God).” The phrase aqim wajhaka can be considered similar to “making an act of islām,” by turning one’s face to God as a gesture of commitment to Him in request of His approval and protection. The phrase “al-dīn al-qayyim” refers to the content of the contract into which man enters, namely the behavior adopted on the right path.

Returning to the interpolated section of Q 5:3, it announces God’s will to take care of those who seek His protection. Concerning the interpretation of the two factitive verbs, akmala and atmama, they designate effects not of time but of quality. The verb akmala, which signals the signing of the contract between man and God and accepting of all its terms, should be understood not as “to complete” but “to make kāmil (perfect).” Likewise, the verb atmama should be understood not as “to finish” but “to make tamām (entire).” Thus I propose the following translations, in French and English:

“Aujourd’hui ceux qui récusent désespèrent [de vous détourner] de la conduite que vous avez adoptée, dīn: ne les craignez pas; c’est moi que vous devez craindre [en raison du Jugement eschatologique annoncé et de ses conséquences]. Aujourd’hui j’ai validé entièrement la conduite que vous devez tenir [eu égard au contrat qui a été conclu]; [en vertu de ce contrat] je vous ai fait bénéficier de ma totale bienfaisance; [et en retour] j’ai agréé le fait que vous vous soyez engagés à vous mettre sous ma protection en adoptant la conduite convenue.”

“Today those who disbelieve are desperate of [leading you away from] the conduct you have adopted (dīnikum). Do not fear them, but fear Me [because of the eschatological Judgment that has been announced and its consequences]. Today I have perfected the behavior by which you are to live [in fulfillment of the contract]. [Following the content of this contract] I made you benefit from My entire good will; [in return] I have agreed to the fact that you have committed yourself to My protection in adopting the right conduct.”

Alternatively, “akmaltu lakum dīnakum wa-atmamtu ʿalaykum niʿmatī” may be rendered: “Today I gave you the best rule of conduct and I fully dispense to you My good will, and I accept the fact that you are committed to adopt this way.”

* Rachid Benzine is a lecturer at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques in Aix en Provence and the Institut Protestant de Theology in Paris, and a research associate at the Observatoire du religieux (Aix en Provence). He is the author of Les nouveaux penseurs de l’islam (Albin Michel, 2008) and Le Coran expliqué aux jeunes (Le Seuil, 2013).

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.