By Vanessa DeGifis

The Qur’an has always been a multi-media corpus, but today’s mobile app technology gives us new dynamic ways to experience the Qur’an as word, image, and sound, and to share these experiences with others. With many schools in the U.S. making iPads available for instructional use, I have been able to use Qur’an apps for iPad and iPhone when teaching my own college-level Qur’an course. A search of “Quran” in the iOS App Store brings up over 2,000 results. Here I compare some key features of two apps that are most popular with students in my Qur’an course and that I use regularly in the classroom and for on-the-go research: iQuran v. 3.3 (30 Jan 2013, Guided Ways Technologies) and Ayat v. 1.0 (17 Apr 2013, King Saud University). Both apps are also available for Android, and Ayat also comes in Mac and Windows desktop formats.

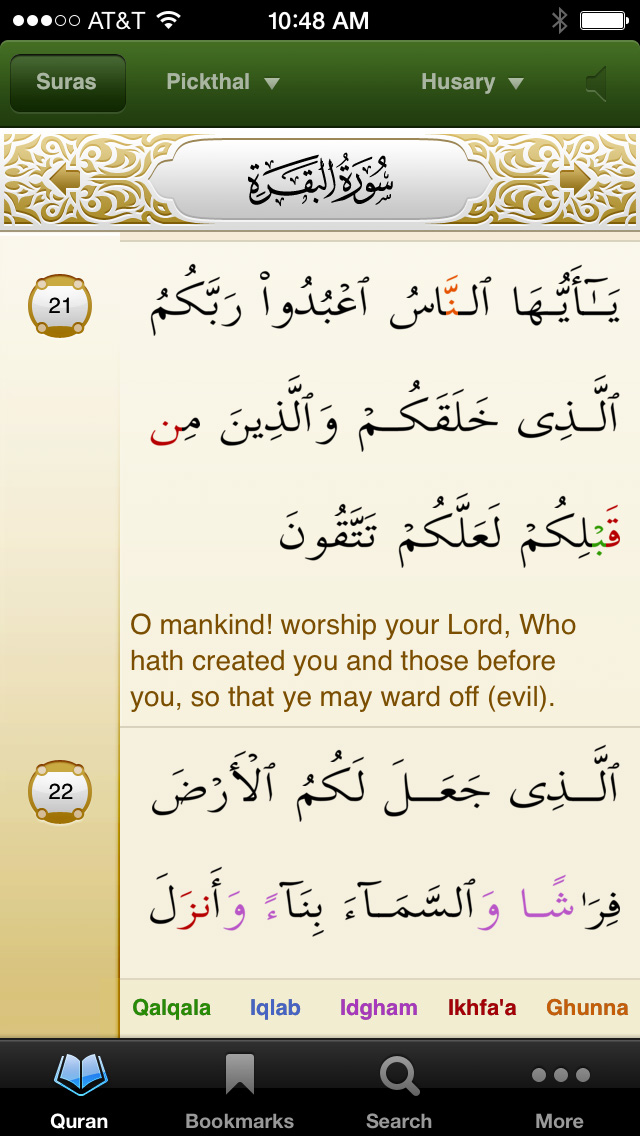

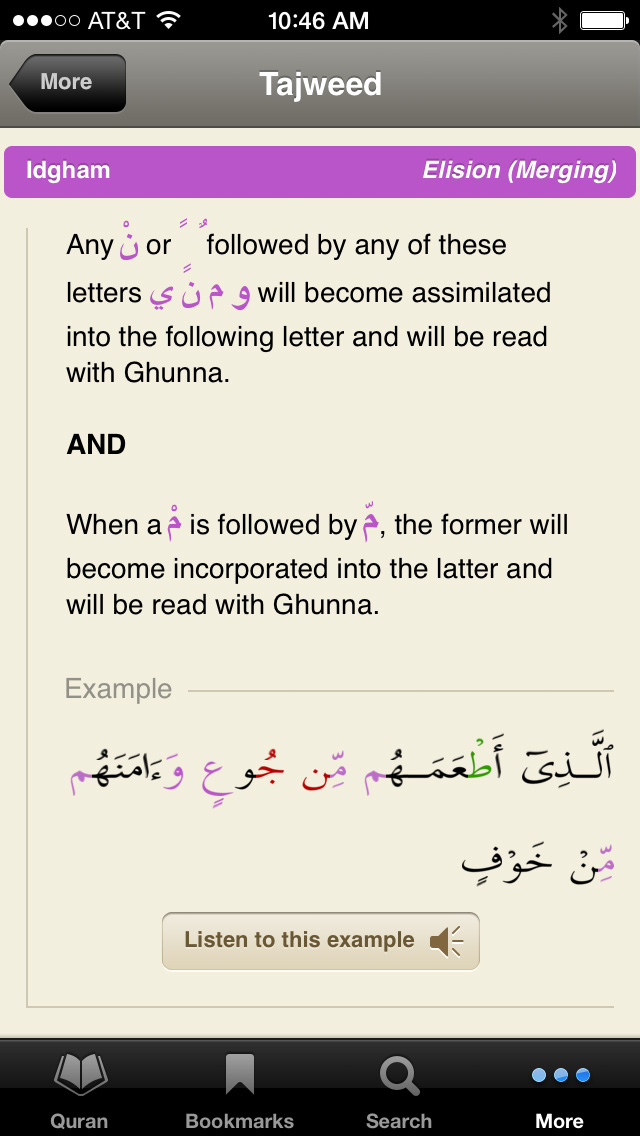

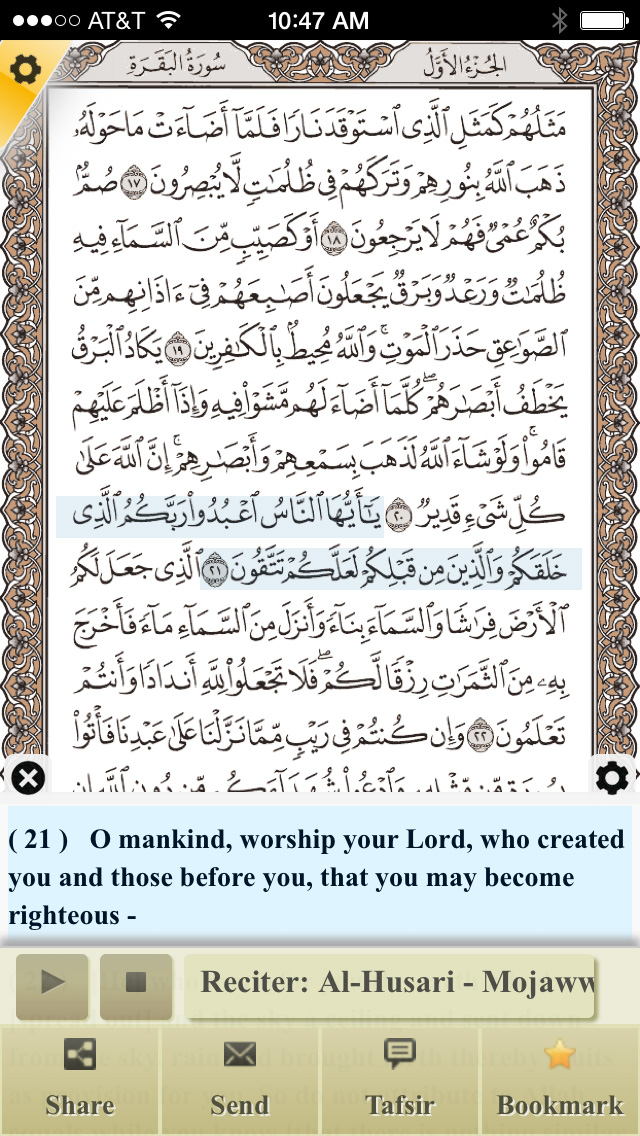

Both iQuran and Ayat provide the complete Arabic text of the Qur’an with full diacritics and sura headings. In iQuran, if you tap the sura heading, it gives the user information on the sura, such as its verse count, its generally accepted order in the chronology of revelation, its order in the canonical text, and its Meccan and/or Medinan origin(s). While both apps provide a fully vocalized Arabic text, in iQuran the text is color-coded for oral recitation(e.g. letters pronounced with qalqala appear in green), accompanied by concise explanations and audio samples of each pronunciation technique. This is useful for practicing or teaching recitation, and helps users to discern more directly and precisely the connections between the Qur’an’s oral performance and its written form. However, Ayat offers nearly three times as many different audio recordings of prominent Qur’an reciters (over 20, compared to iQuran’s eight), including multiple styles from a single reciter (e.g. three versions of Husari). Such a diverse array of audio files allows the user to compare murattal and mujawwad styles as well as the idiosyncrasies of individual performances. Among the various audio files available in Ayat is an audio of English translation, which would be especially useful for English-language users with visual disabilities or who do not understand Arabic but still want a semantically comprehedible aural experience.

Both Ayat and iQuran offer translations in several world languages. For English (the language of instruction for my classes), Ayat offers only one translation, Sahih International, while iQuran offers five popular translations, allowing users to compare multiple interpretive translations and gain a clearer appreciation of the different challenges facing translators as they try to convey literal or figurative meanings, grammatical and stylistic features, etc.

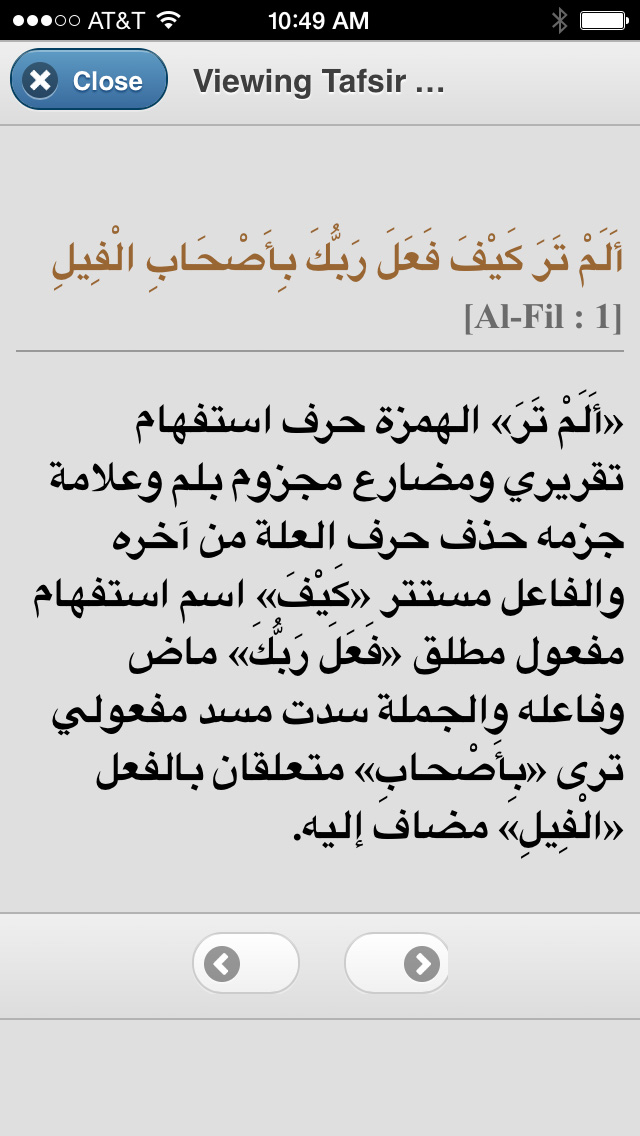

Alongside translations, both apps offer choices of tafsirs. The iQuran app has two tafsir choices: Muyassar and Jalalayn, while Ayat has five, including Tabari and Ibn Kathir, as well as an iʿrab option and an English Tafheem, which can be quite useful since comprehensive verse-by-verse English commentaries are relatively hard to come by. So while iQuran may be more useful for studying interpretive translation, Ayat would be better for studying Qur’anic exegeses.

One of the main reasons why researchers, teachers, and students turn to apps for the Qur’an is that we want convenient interactive search capabilities. While both apps allow the user to search for terms in Arabic, only iQuran allows searching in English. Users must run separate searches for each available English translation, which would seem more or less helpful depending on the purpose of the search. Separate English searches can help the user get a clearer sense of the differences between translations, but without

an integrative list of verses from various translations, it is harder to trace broader networks of scriptural themes. In any case, the ability to search English translations gives iQuran a distinct advantage over Ayat. Another advantage is that iQuran maintains a list of saved searches, including the search term and which text (Arabic, Pickthall, Asad, etc.) was queried. Saved searches make it convenient to toggle back and forth between different searches and compare their results. This function seems to help remediate the disadvantage of separated English language searches. In both apps you can bookmark verses and tag notes on them, but only in iQuran can you group bookmarks according to your task: reading, memorizing, ideating, or discussing. The iQuran app also allows users to share their search results via email, and share verses in Arabic and/or English via text, email, and popular social media. Overall, the iQuran app has more powerful capabilities than Ayat for searching, organizing, and sharing information about the Qur’an text, while Ayat is distinctly better equipped for studying exegeses, grammar, and oral recitations.

I use an LCD cart with speakers and a short-throw projector to share the images and sounds of my iPad with my class, making direct engagement with the Qur’an corpus a central and shared experience. At the same time, most of my students have these apps on their own phones and tablets, so they can directly and creatively interact with the material. Classroom integration of mobile app technology, which most of us are already familiar with and use daily, not only makes discussions more interactive, effective and fun, it also motivates students to explore the Qur’an more independently, even recreationally, outside of class. The portability of mobile apps means that students, teachers, and researchers can conveniently and spontaneously interact with the Qur’an as a dynamic corpus.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.