By David Bertaina

The observation that many Qur’anic passages are dialogical has been apparent to its readers from medieval to modern commentators. Its utterances frequently consist of dialogues between God, its announcer and audience, as well as Biblical and non-Biblical characters. Scholars have devoted substantial attention to character dialogues and the study of genre. However, we have not yet fully exploited the potential relationship between the Qur’an and Late Antique question-and-answer literature.

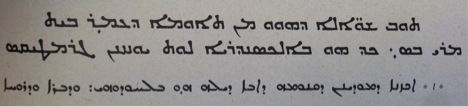

Syriac text (in MS London British Museum Add. 14,533, ca. 8th-9th c.) including twenty-three questions by Thomas the monk in the cloister on Mar Bassos in Egypt to John Philoponus (Yahya al-Nahwi, d. ca. 570). Each question consists of two parts, an orthodox thesis and a Tritheistic antithesis, and ends with a yes-or-no dilemma concerning possible answers.

We might think of the Qur’anic text as divine responses to questioning audiences. Indeed, as Sidney Griffith argues in The Bible in Arabic (2013), the Qur’an insists that it recalls, answers, and corrects earlier Jewish and Christian notions regarding scripture and revelation. For example, Q 2:140 adjudicates between Jews and Christians regarding the true ancestry of the Biblical Patriarchs: “Question: Were Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob, and the Tribes [of Israel] Jews or Christians? Answer: Who knows better, you or God?” In this illustration, the Qur’an recollects a disputation in order to answer it in kind. Why might the Qur’an find this method of question and answer so popular?

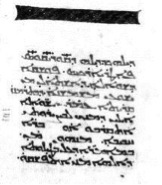

Syriac text (in MS Jerusalem Saint Mark’s Monastery Syriac 129) containing ten questions and answers by Quryaqos of Tagrit, Syrian Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch (793-817), to Deacon Isho of Tarmanaz. This text shows the enduring popularity of the genre. (Image courtesy of David Bertaina)

One suggestion is that the Qur’an found its literary inspiration from the Late Antique context in which it materialized. By the sixth century, Jewish and Christian authors commonly used the question-and-answer genre for instruction, scholarly debates, and oral contests. For instance, 1 Kings 10:1 mentions that the Queen of Sheba tested Solomon with a series of questions during her visit to Jerusalem. Most Jewish, Christian, and Muslim commentaries interpreted these questions to be riddles. But in a Late Antique Syriac question-and-answer text, it begins: “Question: What is your God, and what does he resemble, or to what is he likened?Answer: My God is something from which everything else derives, and is exalted above everything; and he has no comparison, and there is nothing that is like him, because everything (else) is changeable and subject to opposition.” The resonance with passages in Q 112 and 42:11 are remarkable, particularly if we think of 112 as an answer (qul) to a question.

My hope is that more scholars of Qur’anic studies may be interested in exploring the possible role of question-and-answer material in the Qur’an’s development. As a starting point, I would suggest that this process did not consist of direct borrowing or influence from Syriac texts. Nor is it appropriate to reduce Qur’anic material to Syriac or Christian Arabic debates or a mixture of interreligious conversations. Rather, the Qur’an is an active agent that witnessed question-and-answer events, suggesting its familiarity and comfort with Late Antique question-and-answer styles, both in oral and written form. Given that bilingual Arabic-speaking Jews and Christians were familiar with this material, we should not be surprised to witness the Qur’an employ its own arguments in a similar vein.

Further research is needed to grasp the implications of the question-and-answer genre’s relationship to real oral discussions reported in the Qur’an. Likewise we need to understand more fully the ways in which bodies of knowledge were transmitted and transformed via question-and-answer material. The International Qur’anic Studies Association (IQSA) remains an excellent venue for continuing this conversation.

© International Qur’anic Studies Association, 2014. All rights reserved.